Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark review: a surprisingly scary, insightful film - The Verge

Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark review: a surprisingly scary, insightful film - The Verge |

- Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark review: a surprisingly scary, insightful film - The Verge

- 33 Books You’ve Got To Read This Autumn - BuzzFeed News

- The Power of Storytelling: A PEN Ten Interview with Kali Fajardo-Anstine - PEN America

| Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark review: a surprisingly scary, insightful film - The Verge Posted: 09 Aug 2019 12:00 AM PDT With the success of Stranger Things and the new film version of Stephen King's It, nostalgia feels like something of a current horror trope. In these stories, the evocation of childhood fears mixes with pleasurable memories of childhood pop culture, adding a bit of sweet to horror's usual bitterness. At first, the theatrical film Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark looks like it might be following in Stranger Things' footsteps. The first scene is set to the background music of Donovan's wonderful "Season of the Witch," played by a never-seen DJ who recalls Wolfman Jack from American Graffiti. These period touches aren't winking celebrations of childhood, though. The film is set in the past because director André Øvredal has something specific to say about that era and the children who lived in it. The movie is loosely based on Alvin Schwartz's famous collections of short horror stories for kids. A group of friends led by Stella (Zoe Colletti) investigates a haunted house on Halloween. There, they find and take an old book left behind by a long-dead child from a wealthy family. Sarah, now a ghost, starts writing new short stories in the book and the stories come true, resulting in horrible fates for Stella's friends. Stella and her love interest, an out-of-towner named Ramón, try to learn about Sarah's past in order to stop her before her stories do them in. The stories Sarah writes in the book are the parts of the movie based on Schwartz's work. These setpieces are excellent. They have the nightmarish, inevitable illogical logic of folk tales or urban legends. Fans who were terrified as children by narratives of spiders hatching where they're not supposed to hatch will not be disappointed, nor will those who fondly remember the creature who assembles itself from its own severed bits. Harold the scarecrow is particularly effective. Øvredal reminds viewers that you don't really need spectacular makeup or gouts of blood to create a good scare. You can just walk by the same straw-stuffed figure a couple of times and then notice it's not there anymore. The frame story, by contrast, isn't based directly on Schwartz's writing, and it's very different. The narrative of Stella and her friends abandons the book's taut economy for a meandering supernatural slasher. It's like Nightmare on Elm Street with a less visually compelling villain. :no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18956503/ScaryStories2.jpg) It's true that the frame is fairly ruthless in its willingness to do in its characters, especially compared with something like Stranger Things. But it also has themes of reconciliation, forgiveness, healing, and even anti-racism, all of which sit oddly beside the source material's straightforward, scare-the-kids-so-badly-they-never-sleep-again ethos. Colletti and Garza have excellent chemistry; their scenes together sizzle. But is anyone going to this film to see a teen romance, no matter how convincingly portrayed? It was always going to be a challenge to adapt a book of short stories, but Øvredal really seems to have gone out of his way to irritate his core audience. It's an odd choice. Odd choices aren't always bad choices, though. Gradually, it becomes clear that the story Øvredal wants to tell is about childhood trauma — specifically, about what parents do to, and expect from, their children. Stella's mother abandoned her, which is part of why she forms such a quick, unhealthy connection with Sarah, whose parents abused her. One of Stella's friends is attacked after his parents decide to leave him without notice overnight; another is pursued by a hideous, bloated creature who looks like a parody of a pregnant woman. Parents, the movie suggests, are writing their kids' stories, and what they write is death. That may seem paranoid. But in 1968, it was literally true. Those televisions in the background often show images of Vietnam. One shows Richard Nixon, lying as per usual, as he talks about how he doesn't want to drop bombs. This background tale about the necessity of war and the need for men to fight entangles a number of the male characters. One high school kid who disappears prompts his peers to speculate that he may have just gone off to the army early because he was so eager to kill communists. A war story substitutes for a horror story, and at least one of them is the true tale of why a boy isn't coming home. :no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/18956514/ScaryStories3.jpg) The 1968 setting isn't a fun retro jaunt. It's part of the film's meditation on how the world is made up of stories and how those stories trap people. Placing the film in the past is a way of framing it as fiction; it's occurring once upon a time. The true story of the 1968 election is slotted in beside false stories of the supernatural, even as Stella and her friends try to research Sarah's true history, which is eventually written down, then received as a fictional story. Truth and lies slide around each other, tying knots around children's lives. "You don't read the book. The book reads you," Stella declares, in a campy, melodramatic line. But Scary Stories is remarkably insightful and sober in its assessment of the way stories control people, rather than the other way around. "This person is insane, so we can torture her." "That person must go overseas and shoot a stranger." Quentin Tarantino's Once Upon a Time in Hollywood was supposed to be the summer's virtuoso meta-fiction, but its rewritten happy ending, musing on the impotence of writing, seems a lot less bleak than Scary Stories' acknowledgment that some scripts will take you far away where you'll never be seen again. That's not to say that the ending, which clumsily gestures toward a sequel, is perfect — nor, for that matter, is the film as a whole. Like the title says, the movie has more than one tale to tell, and the disjunction in tone and purpose is sometimes jarring or just inexplicable. (Why is there a car chase in this movie?) But Øvredal is to be commended for simultaneously staying true to a beloved franchise and twisting its head around to face in an unexpected direction. Thanks to him, the film isn't just a collection of scary stories. It's a meditation on why the stories we tell ourselves shape us and why that's the scary bit. |

| 33 Books You’ve Got To Read This Autumn - BuzzFeed News Posted: 29 Aug 2019 09:51 AM PDT  Ben Kothe / BuzzFeed News; Courtesy of Caitlin Covington / Via Via Instagram: @cmcoving Courtesy of Tin House Press, Kate Sweeney "How Can Black People Write About Flowers at a Time Like This," is both a question a white woman once posed to her seatmate during a reading Abdurraqib attended in 2016 as well as the name of several recurring poems in the Ohio writer's (and occasional BuzzFeed News contributor's) second poetry collection. The title also sums up the tone of the collection — at turns irreverently funny, angry, and melancholic. Ranging from reflections on heartache and grief to envisioning Marvin Gaye's ghost playing the dozens, the poems are an insistence on exploring the small, mundane joys and sorrows of ordinary life even in the midst of larger political upheaval. Cantoras, Carolina De Robertis (Knopf, 9/3)Knopf, Pamela Denise Harris It's 1977 in Uruguay, and the country is under a military dictatorship. Groups of five or more people can't gather in private spaces without a permit, and while homosexuality isn't outlawed outright, it doesn't need to be, because being an out gay man or woman is an automatic prison sentence. Under these dire straits, five women — ringleader Flaca, activist Romina, housewife Anita, the mysterious Malena, and the teenage Paz — go on an excursion to an isolated beach where they can just be themselves — "cantoras," or women who sing, a code name for lesbians. Over the course of 35 years, De Robertis charts the fortunes of these women as they fall in and out of love and navigate the country's tumultuous politics. That it's written in such lovely prose is an added bonus. Catapult, Anna Leader When writer Dina Nayeri was 15 years old, she became an American citizen. At the swearing-in ceremony, an elderly Indian man screamed into the mic: "I am an American! Finally, I am American." People cheered for him, but for Nayeri, who had left Iran as a refugee with her mother and brother, the moment was bittersweet. "I refuse to deny the simple and vast beauty of it," she writes in her first work of nonfiction, "though I know that they cheered not the old man himself, but his spasm of gratitude, an avowal of transformation into something new, into them." It's this concept that grounds Nayeri's book — an account of not only her own story, going from the privileged daughter of educated professionals to a refugee living in an Italian camp to a fiction writer in Iowa City, but of other desperate asylum-seekers who are expected to perform gratefulness for every act of basic human decency. Why must refugees be good? What does "good" or "deserving" mean, anyway? Riverhead Books, Alessandro Moggi Keret continues his streak of writing short stories that are mordantly funny and bizarre in his latest collection. Take the title story, for instance, a perfect mix of the funny-sads: A father tries to persuade a man not to jump off the roof; the father's kid wants him to jump so he can see the man fly. In another story, "Dad With Mashed Potatoes," a father turns into a rabbit. Discontentment is a recurring theme throughout ("Life is like an ugly low table left in your living room by the previous tenant") — but threaded through his sense of humor, you feel a little less lonely, a little more light. Flatiron Books, Alex Tabar Photography "The first time Juan Ruiz proposes, I'm eleven years old, skinny and flat-chested," Ana Canción, the narrator of Cruz's third novel, informs us on the first page. It's a harbinger of things to come for Ana, who marries Juan four years later in a business deal arranged by her parents. Whisked away from the Dominican Republic to New York City in the late '60s, Ana must reckon with her own loneliness, her drunken cheating husband, and her homesickness. Though the plot points are grim, Cruz tells the story with a raucous sense of humor and writes in short, present-tense chapters that help make this a propulsive though heartbreaking read. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Stacy Liu What drives a man to murder? Backbreaking physical labor and untenable poverty caused in part by pollution and climate change, suggests Booker finalist Tash Aw in his latest novel. Ah Hock, a poor, middle-aged Chinese Malaysian man, spent three years in prison after murdering a migrant worker. But why did he do it? Structured as a series of long interviews he does with a young graduate student, Hock narrates his life story and the story of so many other working poor people who travel to richer Asian countries in hazardous conditions, taking on dangerous jobs. "They didn't understand that it wasn't the pay that destroyed the spirits of these men and women, it was the work — the way it broke their bodies before they could even contemplate the question of salaries. The way it turned them from children to withered old creatures in the space of a few years," writes Aw. For an inside view of the folks globalization has left behind, this book is essential. Mulholland Books, Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times A follow-up to her Edgar Award–winning 2017 novel Bluebird, Bluebird, Locke's new novel is a mystery ripe for this age. Set soon after the 2016 election, 9-year-old Levi King has gone missing and the police suspect his family of white supremacists might finally be pinned down if they can figure out where the boy is. On the case is Texas Ranger Darren Matthews, whose previous escapades had driven him to alcoholism and almost ruined his marriage. What makes Locke's mysteries so good (she's a writer for TV's Empire too) is her ability to conjure up a mood with vivid prose. Her depiction of Texas is so evocative you can practically hear the beer cans cracking open and smell the swamp water. Akashic Books, Courtesy of Akashic Books Forbes' fifth novel is an epic tale of two soulmates: Moshe Fisher, born with mismatched eyes and pale skin that bruises easily, and Arrienne Christie, "her skin even at birth the color of the wettest molasses, with a purple tinge under the surface." Arrienne is his protector at school — and later his lover— but how they eventually wind up together is part of this unconventionally crafted story that spans decades, from the years before Jamaica's independence to the 2010s. Forbes' sentences are the stars here; it's a book that rewards slow, careful reading. Salt Slow, Julia Armfield (Flatiron Books, 10/8)Flatiron Books, Sophie Davidson Already published earlier this year in the UK, Armfield's short story debut immediately calls to mind the slippery short stories of Carmen Maria Machado and Angela Carter in its gothic treatment of common girlish concerns, from puberty — a girl's skin literally molts right before she's kissed — to boyfriends who turn to stone. It's the kind of quiet, meticulously crafted collection that's a sign of even greater writing to come. Simon & Schuster, Jon Premosch Expanding on some of the themes laid out in his 2012 Rumpus essay about a sexual encounter with a straight man that goes scarily wrong, Jones (full disclosure: a former BuzzFeed News employee) barges right into the coming-of-age memoir pantheon with this slim account of growing up gay and black in Texas with a determined single mother and a religious grandmother. Toni Morrison famously said to write the book you want to read; in this tender sexual reckoning, it feels like Jones wrote a book to his teenage self. The good news for the rest of us is that we get to read it. Random House, Leonardo Cendamo The lovable, irascible Olive Kitteridge is back in this sequel to the charming (but also casually devastating) 2008 novel that won a Pulitzer Prize and spawned an HBO miniseries. Strout sticks to her winning formula: interrelated short stories linked by the presence of familiar faces, from Olive, who, like before, is sometimes a major character, other times a more supporting one, to Jack Kennison, the widowed Republican whose gay daughter hates him. Strout writes about loneliness and estrangement with uncanny accuracy; look at the work of this parenthetical after Olive reveals that her daughter-in-law had a stillbirth: "'No reason to cry about it,' Olive said. (Olive had cried. She had cried like a newborn baby when she hung up the phone from Christopher after he told her.)" In this novel — set against the backdrop of a rapidly changing Maine, ravaged by opioid addiction and economic neglect — Strout wields great pathos out of life and all its attendant tragedies. HMH, Julia Cumes The premise of one of the fall's buzziest memoirs is bananas: When author Adrienne Brodeur was 14 years old, her mother, Malabar, crept into her room late one night and asked if she could keep a secret. She had just kissed Ben, their married family friend, and she needed Adrienne's help facilitating an affair. For the next several years, Adrienne and her mother conspired to keep Adrienne's ailing stepfather and Ben's wife in the dark as Malabar and Ben carried out their tryst. With its privileged, WASP-y setting off of Cape Cod, it's the kind of juicy what-is-happening memoir that just begs to be made into a movie. Luckily for us, the film rights have already been sold. Ecco, Maria Kanevskaya In 1991, a 51-year-old Korean-born woman and convenience store owner named Soon Ja Du shot a 15-year-old black girl named Latasha Harlins in the back of the head after accusing her of stealing a bottle of orange juice. Video footage later showed Harlins had the change for the orange juice in her left hand. A few months later, the burning and looting triggered by the Rodney King beating would engulf Los Angeles. Known for her mysteries, Cha uses this incendiary real-life event as the basis for her latest novel. She alternates between the points of view of Shawn Matthews, a fortysomething ex-felon whose sister Ava was killed by a Korean convenience store clerk, and Grace Park, a 27-year-old pharmacist who doesn't understand why her older sister and mother are estranged. It's an extremely delicate subject matter, and Cha does a masterful job imbuing each character with nuance and care. Little, Brown, Sam Richardson The title of this short, poignant memoir is effective on many levels — particularly as a nod to the famous last name that inevitably, though perhaps unfairly, influences coverage of this book. (Dunham is the younger sibling of Lena Dunham, and their parents are the successful artists Laurie Simmons and Carroll Dunham.) But it's also an apt summary of the years Dunham spent unmoored and unsure of their own gender identity, not feeling like a woman, but afraid of the implications of choosing to live as a man. "I hesitate to call the exhaustive day-to-day of embodiment 'dysphoria,' that catchall for the pain of having a body that doesn't align with one's sense of self," writes Dunham. "And if I admitted I was dysphoric, I'd have to deal with the fallout. I'd have to decide whether to do something about it." Eventually, Dunham does "do something about it," but the journey they take to reach that point is an honest, reflective reckoning well worth reading. Arias, Sharon Olds (Knopf, 10/17)Knopf, Hilary Stone Olds has the goods in this eclectic collection of new verse, which runs the gamut from reflections on anal sex: "...If my mom had not beat me while I / clenched my butt as if to keep her out, / I might have liked the asshole more, I might / want to kiss it!" to the peculiar grief of meeting an ex-husband, "... and then / one went one way, / one another, / one in sheer relief, one / in grieving relief," to Trayvon Martin, a reference that, in a smart sequential move, she turns on its head in "Looking South at Lower Manhattan, Where the Towers Had Been": "If you see me starting to talk about / something I know nothing about, / like the death of someone who's a stranger to me, / step between me and language." With its expansive range and warm honesty, this book shows us why the Pulitzer Prize winner is still among the most beloved poets alive. HMH, Zach Smith None of the adult family members — firstborn daughter Alex, mother Barbra, son Gary, and his wife Twyla — seem especially devastated that their patriarch, businessman Victor Tuchman, is dying. The reasons for their lack of emotion slowly unfold over the course of one long day in New Orleans as Attenberg shifts character perspective from chapter to chapter, jumping between the present and the past. Complicated families are Attenberg's speciality, and she more than delivers on that premise here. Ecco, Leigh Anne Couch Weird, funny, but also unexpectedly moving, Wilson's latest novel has an unusual premise: Lillian is a 28-year-old salesclerk living in her mother's attic when she gets a phone call from an old high school friend, Madison. Both beautiful and rich, Madison needs Lillian's help watching over her two oddball stepchildren, Bessie and Roland, who have a bad habit of catching on fire whenever they are upset. Unblinking, Wilson takes this premise and rolls with it. Lillian's blunt narration paired with the twins' dark childhood make the book an affecting reflection on the blithe cruelty of the rich and what it means to be a good parent. Find Me, André Aciman (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 10/29)Chris Ferguson The good news is that you don't have to have read Call Me by Your Name, Aciman's 2007 bestselling novel turned Oscar-nominated movie, to immediately fall in love with this sexy, melancholic follow-up. It stands entirely separate, yet connected, a beautiful ode to the passage of time, to the lasting power of true love and the ache of loneliness even when coupled up. Ordinarily, this would be the part of the write-up where I tell you what Elio and Oliver have been up to since their transformative summer in that Italian villa all those years ago, but this novel is best read cold, the revelations about who these characters have become unraveling slowly like a gorgeous piece of classical music. Jorge I. Cotte "This is a book about black aesthetics without black people," writes Jackson (an occasional BuzzFeed News contributor) in the introduction of her debut work of cultural criticism. It's an effective summary of the book, which tackles the slippery concept of cultural appropriation in everything from the rise and fall of Vine (RIP) to the proliferation of Real Housewives of Atlanta reaction GIFs online. Amid the deluge of thinkpieces on this topic, Jackson's writing is a beacon of nuance — smart, funny, and engaging on the recent controversies of the past decade or so. Feed, Tommy Pico (Tin House, 11/5)Niqui Carter Teebs, the junk food–loving, commitment-phobic, Extremely Online, Kumeyaay Nation alter ego of the poet Tommy Pico, makes his final appearance in Pico's latest book of poetry. On book tour, more successful than ever, Teebs is learning the ancient truth that "success doesn't lance to happiness," as he grapples with bad dates, loneliness, and general despair amid an unending stream of bad world news. Pico writes with his trademark irreverent sense of humor: ("A hot person farts on the tarmac and gets super embarrassed and I'm / like this is what it sounds like when doves cry," but his lines can still hit like a gut punch: "Is it revolutionary, asserting the desire to continue? Well, / it certainly is new." Graywolf Press, Art Streiber / AUGUST "I never read prologues. I find them tedious. If it's so important, why relegate to the paratext? What is the author trying to hide?" so begins Machado's beguiling, unconventional memoir about her abusive romantic relationship with a woman. (Well, it's actually one of many beginnings.) Known for her dark, twisty short stories in the 2016 National Book finalist Her Body and Other Parties, Machado rejects standard memoir conventions in favor of short discursive chapters that include pontifications on her favorite Disney villains, quotes from academic theorists, and choose-your-own-adventure reenactments. The result is a thoroughly engrossing, sometimes enraging must-read. Other buzzy books coming out this fall: Salman Rushdie's Quichotte (Random House, 9/3), a modern retelling of Don Quixote; Margaret Atwood's highly anticipated sequel to The Handmaid's Tale, The Testaments (Nan A. Talese, 9/10); Petina Gappah's fictionalized 19th-century narrative of the English doctor David Livingstone's journey out of what is now modern-day Zambia, as told by two of his black African servants, Out of Darkness, Shining Light (Scribner, 9/10); Jacqueline Woodson's Brooklyn-set family drama Red at the Bone (Riverhead, 9/17); Rachel Cusk's newest collection of nonfiction, Coventry (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 9/17), Ann Patchett's The Dutch House (HarperCollins, 9/24), a decades-spanning novel about a rich Philadelphia family in the turn of the century; Patti Smith's latest memoir, Year of the Monkey (Knopf, 9/24); Ta-Nehisi Coates's debut novel, the speculative fiction slave saga The Water Dancer (One World, 9/24); Leslie Jamison's latest essay collection, Make It Scream, Make It Burn (Little, Brown 9/24); Ben Lerner's novel The Topeka School (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 10/1), about a brilliant debate student set in 1980s Kansas; Zadie Smith's first short story collection, Grand Union (Penguin Press, 10/8); and Margaret Wilkerson Sexton's sophomore effort about three generations of black women from New Orleans, The Revisioners (Counterpoint Press, 11/5). |

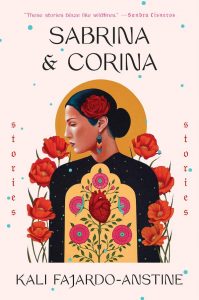

| The Power of Storytelling: A PEN Ten Interview with Kali Fajardo-Anstine - PEN America Posted: 29 Aug 2019 02:00 AM PDT

The PEN Ten is PEN America's weekly interview series. This week, PEN America's Public Programs Manager Lily Philpott speaks with Kali Fajardo-Anstine, author of the short story collection Sabrina & Corina (One World, 2019). 1. What was the first book or piece of writing that had a profound impact on you? This moment changed me. I remember feeling that truly great literature was medicine with the ability connect people across cultures, classes, and nations. Sandra Cisneros's work allowed me to see the power in my culture's storytelling tradition, and allowed me to see the power within myself. 2. How does your writing navigate truth? What is the relationship between truth and fiction? My father recently sent me an email with no context. It was a quote from Gabriel García Márquez's The Autumn of the Patriarch: "A lie is more comfortable than doubt, more useful than love, more lasting than truth."

3. What does your creative process look like? How do you maintain momentum and remain inspired? My current process for my forthcoming novel is more personally sustainable. Some years ago, I created a detailed scene-by-scene outline of the entire book. I work off this outline, adjusting accordingly. I am not able to write every day due to touring and the emotional anarchy of daily life, but when I do write, I often go away, setting aside devoted time for a project. In this mode, I write at least a 1,000 words a day and I make handwritten notes, visualizing each scene before I commit to writing sentences on the computer. In terms of inspiration, I treat my life as inspiration and I am open to experiences, to coincidences, to watching for signs. This allows my deeper mind to work on future stories and novels that may or may not ever be written. 5. What is your favorite bookstore, or library? These are some Colorado bookstores I adore: Marias Bookshop in Durango, Townie Books in Crested Butte, and West Side Books, Tattered Cover, and Book Bar in Denver. In terms of libraries, my home library, Denver Public Library, holds my heart. I love visiting the Western History/Genealogy Department, where the archivists and librarians welcome me with open arms, always ready and willing to assist with research.

6. How does your identity shape your writing? How does the history carried by the elders in your family affect your identity, and in turn, your writing? 7. What is the most daring thing you've ever put into words? 8. What advice do you have for young Latinx writers? 9. Which writer, living or dead, would you most like to meet? What would you like to discuss? I would love to discuss craft, time in fiction, the short story form, and the way she renders the lives of women in her stories. But I think, in many ways, when meeting writers whom I admire, I simply want to experience their being. What kinds of stories would she tell over lunch? What draws her eye? Any knowledge offered is a gift. Kali Fajardo-Anstine is from Denver, Colorado. Her fiction has appeared in The American Scholar, Boston Review, Bellevue Literary Review, The Idaho Review, Southwestern American Literature, and elsewhere. Kali has received fellowships from MacDowell Colony, the Corporation of Yaddo, and Hedgebrook. She received her MFA from the University of Wyoming and has lived across the country, from Durango, Colorado, to Key West, Florida. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "famous short story,short stories for high school" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment