ehextra.com - Ehextra

ehextra.com - Ehextra |

- ehextra.com - Ehextra

- 'It was like a movie': the high school students who uncovered a toxic waste scandal - The Guardian

- Breaking New Ground: Black History Month is a good time to recognize the work of underappreciated artists - Florida Courier

| Posted: 26 Feb 2020 10:01 PM PST [unable to retrieve full-text content]ehextra.com Ehextra |

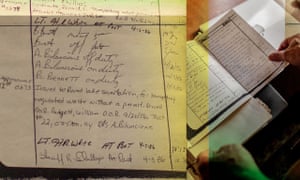

| Posted: 01 Feb 2020 12:00 AM PST In the summer of 1991, Middletown high school, roughly 70 miles north of Manhattan in New York's verdant Orange County, acquired a handful of video cameras. The goal was to train the school's teenage students in film-making and media production, using local subjects as a starting point – perhaps a documentary about the city's sports teams or an amateur talkshow. Instead, under the tutelage of Middletown high's popular English teacher, Fred Isseks, a rowdy and diverse group of teenagers organised themselves into an investigative journalism unit. Officially, Isseks' class was open only to the school's oldest students, aged 16 to 18 – but, unofficially, it welcomed everyone. Kids not even enrolled in the course joined Isseks' students in shooting short films. The teenagers alternated between grungy early-90s flannel and choker necklaces and awkward attempts at business attire as they honed their reporting skills. They invited local representatives into the school's new media studio for a political debate, and covered topics such as the city's curfew for teens. One former student joked to me that the class became a surreal mix of "rap videos and corrupt politicians". Over the next six years, culminating in 1997, students passing through Isseks' high school class would film, edit, and release a feature-length documentary that exposed a generation's worth of illegal, mob-connected dumping of toxic materials in their part of New York state. Industrial solvents, liquid refrigerants, crushed battery casings, petroleum additives, printing inks and untreated medical waste, including radioactive isotopes: it all flooded the landfills around Middletown, constructed without ground liners, atop freshwater aquifers that fed the region's drinking wells. As a retired compactor operator explains to Isseks' students in the film, sometimes there was so much bloody hospital waste on the ground, it looked as if he had run someone over. Another interviewee, a former driver for a mafia-owned waste-hauling firm, described tipping fuming truckloads of paint sludge from a nearby automobile factory straight into the dump. Middletown residents were told it was all just certified municipal waste. Isseks' course, known as Electronic English, would propel many of its students into careers in media production and environmental law, but at the time their work did not receive universal approval. There were warnings of arrest from the county sheriff; near-total disinterest from the city's local newspaper; public frustration from regional politicians; and at least one death threat. David Birmingham, now 42, is a former student of Isseks' who graduated from Middletown high in 1995. He lives in town with his wife and four children; their eldest daughter graduated from the school in 2019. "In the beginning, I just thought it was too fantastical to be true," Birmingham says. "To me, it was like: there's no way there's a toxic waste dump basically in my backyard. There's no way all these politicians I see on TV are actually covering something up. It seemed like a movie – like this couldn't happen here. People would tell me, 'You know, this isn't what you think it is.' But, as it turned out, it was exactly what we thought it was."  While Isseks' class suggests an early affinity with today's youth climate activists, it also relied upon slightly different tactics, based not in protest or spectacle, but documentation. As Birmingham describes it to me, it was about showing up, over and over again, at local meetings, relentlessly filing freedom of information requests, and, importantly, getting things on film. Nevertheless, the question seems to haunt both Isseks and Birmingham: what did the documentary achieve? Is Middletown, as a community, safer today because of the students' work? *** Middletown sits amid rich, rolling agricultural lands and mountains with biblical names, such as Mount Adam and Mount Eve. The financial magazine Kiplinger routinely rates it as an idyllic place to raise a family, and an equally inviting place to retire. Humans have long been seduced by the region: 12,500-year-old indigenous archaeological sites have been discovered here, some of the oldest known in North America. Just outside the city are synthetic landforms that swelled into being in the 1960s. These unearthly blisters, together occupying an area more than three times the size of Disneyland, California, loom over the surrounding fields and forests. They are the county's landfills, built to contain only municipal household waste. However, as the students' documentary discovered, and sworn legal testimony taken in the 1990s made explicit, this was by no means the case. The landfills accepted anything and everything, from customers hundreds of miles away in Pennsylvania and Ohio, sometimes in the middle of the night, when the landfill gates were left unlocked. Although some of the dumps investigated by the students were as far as 15 miles outside Middletown – on land within the boundaries of neighbouring municipalities –others were right down the hill, along the banks of the Wallkill River. It was the residents of Middletown, a city of more than 25,000, who found themselves directly in the centre of them all. Isseks, 71, still lives in Middletown with his wife, Denise. Their daughter graduated from Middletown high in 2010; Isseks retired from teaching the following year. Isseks is himself a 1966 graduate of the school; his senior yearbook describes him as "intelligent and sincere, with a streak of devil in him". While teaching at Middletown in 2003, Isseks earned a PhD in communications from the European graduate school in Switzerland, whose celebrity faculty has included Slavoj Zizek and Judith Butler. Isseks's thesis, Media Courage, includes a chapter on the philosophical potential of the American high school system. His belief that teenagers need to be given work with genuine meaning and consequence in the world would shape his entire teaching career and, in the process, change his students' lives. Reflecting on the project today, Isseks places the county's three major landfills – the Town of Wallkill, Orange County, and Al Turi landfills – in the context of geology, not cultural theory. During the last ice age, he explains, massive glaciers sculpted the land into the gentle bowls and valleys that would later be so appealing to Middletown's 20th-century landfill entrepreneurs. Landscape, for Isseks, is drama solidified. When we meet, he is wearing a T-shirt with the geological ages of the Earth depicted in a colourful graphic on its front. (Later, after a boozy dinner, Isseks is able to recite the eras of the Earth backwards, from memory, making only one minor error.) The students' documentary originated from a passing comment. In 1991, Isseks tells me, he heard from an environmentalist friend that former employees at the Town of Wallkill dump had unsettling stories to tell – and that a few were willing to speak on the record. Isseks asked his students if they might be interested in interviewing the men. To his delight, several said yes. The resulting hour-long film, titled Garbage, Gangsters And Greed, opens with an interview with former bulldozer operator Donald "Dutch" Smith. At the time, Smith lived in a trailer just outside the Wallkill landfill gates. "I tell you," he says, speaking to the camera as birdsong trills in the background, "there's thousands and thousands of tonnes of toxic waste in there, of anything you can name, from radioactive to hospital waste". Smith's words are followed by shots of rust-coloured leachate pooling on the soil: unidentified chemicals oozing from the waste mass. "You name it, it's in that landfill – and I know it's in there, because I buried lots of it." The town's supervisor at the time, Howard Mills, described by the local newspaper as a "Republican icon", admits later in the film that this was not an exaggeration. "It's absolutely correct that there is a tremendous amount of toxic waste remaining in that landfill… We make no attempt to deny that," Mills says, flanked by county officials. "This is a dangerous landfill." The documentary is a mix of handheld footage, produced during various acts of trespass at the county's landfills, and formal, on-camera interviews with politicians and retired landfill workers, often staged in the high school's recording studio. One of the students' most shocking discoveries comes during an interview with Dieter Bohnwagner, a stocky, mullet-haired former worker at the Orange County landfill. In the film, Bohnwagner admits there is a "hidden landfill" on Orange County land, somewhere in the woods beyond the sixth fairway of a local publicly owned golf course. Trespassing across the course – and filming themselves every step of the way, as golfers play in the background – the students locate this illegal dump, finding a dozen crushed, 55-gallon chemical drums half-buried in the earth. Isseks shows me a letter he received from Orange County representatives after he informed them of his students' discovery: rather than offer thanks for locating a site of potential risk to the Middletown community, it threatened Isseks and his students with arrest should they ever attempt to return. (One of Isseks' former students suggests to me that perhaps this response was not unfair: Isseks, at the very least, was not discouraging minors under his supervision from trespassing and publicly antagonising figures allegedly connected to the New York mafia.) For his part, Isseks insists that he went out of his way to ensure his students' safety, often bringing other adults along on excursions. He also made sure the students' parents knew exactly what the class was up to and when, becoming long-term friends with many in the process. In one interview that did not make it into the film, Isseks tells me, Bohnwagner also claimed that a fairway at the same golf course had been built over a dumping ground for household appliances. Hundreds of refrigerators, leaking toxic CFCs, allegedly lie underground there. Facing what he interpreted as professional retaliation for complaining about conditions at the landfill, Bohnwagner also threatened to reveal the location of something called "the tomb". The tomb, he claimed, was an unlined pit into which chemical waste had been dumped, inside a local, publicly owned park. Whether or not Bohnwagner's tomb, or those hundreds of discarded refrigerators, even exist is unclear; when I ask the parks commissioner for Orange County about these allegations, he responds that this is the first time he has ever heard such rumours.  Perhaps the group's most significant feat of reporting came in June 1996, when a Middletown sheriff's lieutenant escorted Isseks and two female students into the county's sheriff station. They were attempting to discover the truth about a logbook from the Wallkill landfill. In the late 1980s, a burglar had broken in late at night, it was claimed, and, improbably, stolen this notebook: the only record of what had been dumped and buried there – and by whom. According to Isseks, he and his teenage students had made multiple, formal requests for information about the book for two years; the sheriff's office consistently replied that no such notebook existed. The lieutenant led the group into the station's storage facility. He opened a document box, reached inside, and said, "This is what you're looking for, right?" Out came the missing logbook. He encouraged the students to take it home – and to copy it. The book contained meticulous handwritten notes by Orange County sheriffs' deputies, stationed at the nearby Town of Wallkill dump. Over hundreds of entries, they had documented the illegal burial of toxic waste in a landfill meant only to receive municipal rubbish. What's more, the log confirmed that much of this dumping had been done by haulage firms connected to the East Coast mob, including one owned by the Mongelli organised crime family. (Louis Mongelli Sr, former owner of Orange County Sanitation, had allegedly disappeared into the federal witness protection program in 1994.) The deputies had also noted every single ticket they'd written to drivers hauling prohibited loads – though, to the deputies' frustration, most of these tickets simply disappeared, unpaid, never to be submitted to local courts. For Isseks and his students, the logbook was undeniable proof of illegality – not just evidence of toxic dumping, but of collusion between town officials and corrupt waste-hauling firms. More importantly, Isseks tells me, the book's mysterious reappearance in the sheriff's archive was a sign that the students' efforts were succeeding. Even the deputies now seemed to be on their side, accelerating a sense that the city wanted its toxic secrets unearthed. *** By the mid-90s, the students' documentary had picked up political steam. Birmingham tells me that he grew accustomed to seeing local politicians annoyed at the students, irritated by Birmingham's own habit of showing up to film town hall meetings, filing endless freedom of information requests. One evening in spring 1994, though, a politician pulled Birmingham aside and asked for an update. What was going on at the landfills? What had the students found out? An unruly group of trespassing teenagers had quietly become the best news source in town. Their most powerful ally would prove to be New York state representative Maurice Hinchey. As Hinchey and others had shown, mob connections to illegal dumping were by no means limited to the landfills around Middletown. In Poisoning For Profit: The Mafia And Toxic Waste In America, published in 1985, authors Alan A Block and Frank R Scarpitti documented similar scenarios across the US. Some haulage firms, they wrote, deliberately stockpiled trucks filled with liquid toxins, waiting for rainy days; their drivers would then circle around on local freeways with their valves open, draining hazardous chemicals directly on to the roadbed. One driver boasted that "the only way I can get caught is if the windshield wipers or the tires of the car behind me start melting". Other mob-owned companies would mix liquid waste with home heating oil, meaning that unwitting customers could stay warm in the winter, while burning toxic waste at the same time. Some businesses would "cocktail" their wastes with construction debris, allowing crushed drywall, lumber and other porous building materials to absorb dangerous chemicals. (In 1995, the Town of Wallkill landfill was capped using just such construction debris.) These mafia associations began to worry some of Isseks' students. One member of the class, speaking to me on condition of anonymity, describes receiving a death threat. The student was pulled aside at a late-night "field party" – an outdoor get-together – by the adult son of a local politician. Drunk, the man warned Isseks' student to "leave the landfill alone". The man went on to falsely claim that he was suffering from terminal cancer, adding that he "wasn't afraid to take someone with him". Sufficiently spooked, the student dropped Isseks' class. Another student vividly recalls being followed home after an afternoon filming at the dump, by a car they had seen parked outside the landfill gates. These experiences contributed to a sense among the students that they might be getting in over their heads. For Hinchey, who died in November 2017, the Middletown high school students' dedication was a shot in the arm; in the documentary, he seems energised. He even launched a new round of public hearings in the town of Wallkill, questioning former landfill employees, among other witnesses, about what had really been buried near Middletown – testimonies that further fuelled the students' reporting. It was in 1993, however, that the class had perhaps its ultimate brush with power. The students were invited to attend an event at Stewart Air National Guard Base where they would meet President Bill Clinton. Birmingham took advantage of the opportunity to hand the president a VHS tape with an early cut of their documentary. Despite Clinton's thumbs-up, the narrator of this scene drily remarks that the students received no official response. Four years later, in 1997, when the final cut of their documentary was released, the question of the landfills' long-term effects – and the Middletown community's safety – remained unanswered. Hoping to better understand the students' legacy, I visited New York state wildlife pathologist Ward Stone at an assisted-living facility in upstate New York, where he has retired. Stone, who participated in the documentary, is a broad-shouldered former football player unafraid of corporate power. Knocked down by a series of strokes, he remains, in his words, "a fighter". In the film, we see Stone standing in the road, hands on his hips, loudly arguing with a landfill official; his attempts to run chemical tests had been consistently thwarted, his samples physically confiscated by police. "Pursue the chemicals," Stone urges me, insisting that the story of these landfills is far from over, their legacy now hidden in the bodies of local animals, from birds to fish. The New York Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC), Stone's former employer, confims that since Stone's time the DEC "has not conducted any investigations of contaminant levels in wildlife associated with closed landfills in the Wallkill River watershed". *** Isseks is still in close contact with many of the students who passed through his classroom. Even those he has not kept in touch with remember him fondly: when we go out for dinner at a local pizza restaurant, a man sitting several tables away recognises him, offers an effusive hello, and explains that he took Isseks' English class in the late 80s. Rachel Raimist was one of the first students to get involved in the landfill documentary. At the time, Raimist tells me, she was just another bored teenager, with dyed hair, a pair of battered Doc Martens, and an interest in photography. One day, she and a friend decided to skip class and go to Burger King. On their way across the parking lot, they ran into Isseks. His response was disappointed, rather than disciplinary, and she credits his intervention with changing her life. "You shouldn't be cutting class," she remembers Isseks saying, "you should be taking Electronic English." Curious, Raimist signed up, and within days was helping to uncover her town's buried secrets. "I loved the power of telling stories and getting adults upset," she says with a laugh. Raimist now works in television, and even has a media lab named after her at the University of Minnesota, the Rachel Raimist Feminist Media Center. "I would not be directing television now if it wasn't for Fred," she says. "Fred had a huge influence on who I am, and how I see the world."  Another former student, Jeff Dutemple (class of 1994), works as a camera operator on shows including Apple TV's Dickinson. "I think there are more people I worked with on those documentaries in high school who still work in film and television than the people I went to film school with," he says. Jon Gunther, who graduated in 2000, and took Isseks' course early in his high school years, now practises environmental law. Although all three major landfills explored in the documentary are now closed and no longer receive waste of any kind, concern about their impact on the region persists. Today, Isseks has new allies. Susan Cleaver is a photographer and environmental activist based in Goshen, 10 miles from Middletown. Concerned that the DEC has not done enough to monitor for pollutants, and alarmed by rumours of local health issues potentially connected to the landfills, Cleaver has funded a series of water-quality tests along the Wallkill River. She shows me three-ring binders stuffed with test results and photographs, including long lists of chemical elements and their concentrations in the water. High levels of ammonia, arsenic and magnesium, among dozens of chemicals, have been detected. One of the worst of these is toluene, a petrol additive and potent nerve toxin, according to former Orange County legislator Tom Pahucki. Pahucki served in local government from 1994-2013, and still lives in the area, where he now works as a real estate broker. When he stood for the first time, Pahucki says, it was a "single-issue election": you either agreed with his opponent, who sought to reopen and even expand the county's landfills, or you wanted to close those facilities entirely. Although the landfills had been a dependable source of local employment, Pahucki won, signalling a clear shift in opinion, fuelled in no small part by Isseks' students, who had been broadcasting their in-progress documentary on a local television channel. Just a few months after being elected, in 1994, Pahucki was alerted to something strange happening along the edge of the landfill, on the banks of the Wallkill River. The trees were falling over – in the wrong direction. Rather than leaning toward the water, as the ground around them eroded, they were instead falling back toward the landfill, evidence that their roots were being pushed out from beneath. The landfill was slumping. Alarmed, Pahucki pointed this out to Orange County engineers. When he came back a few weeks later to see if anything had changed, someone had simply cut down the trees. "That's how we do things," Pahucki says, disappointed. "You got a problem with the trees? Well, we'll just cut them down." *** In October 2019, Isseks, Cleaver, Birmingham and I go for a long hike along the Wallkill River, scrambling through thick growth across from the Orange County landfill. At one point, a DEC employee arrives and begins taking photographs of us from the opposite river bank. Throughout the afternoon, Birmingham seems nostalgic. Now a family man, running his own tutoring business, Birmingham tells me that Isseks' class awakened in him a passion for environmental conservation. "I remember coming home just generally muddy and dirty, and sometimes smelling a little like a dump," Birmingham says. For him and his fellow students, the mud, ticks and ruined shoes were a source of pride, an essential part of fact-checking what the adults in town had been telling them. "Still, after all these years," Birmingham says, referring specifically to the Wallkill landfill, "it boggles my mind what they were going to do with that place. They were literally going to plant grass on top of a known toxic waste dump and build a park and an adjacent school." That this never came to pass is at least one strike in the documentary's favour. Although there are no leachate streams visible on our hike, Cleaver notes that previously prominent mounds of rip-rap – dry stone rubble that had been dropped along the edge of the landfill to prevent it from slumping – have disappeared below the waterline. She and Isseks both interpret this as a sign of potential structural failure. For Isseks, the nightmare scenario is that a hurricane or tropical storm – such as Sandy, which dramatically flooded New York City in 2012 – could hit the region, saturating the landfills from below and leading to their collapse. One or both of the Orange County and Al Turi landfills could then slide into and block the Wallkill River. Contaminated waters would back up, flooding tens of thousands of acres of productive farmland with toxins. (Asked about this scenario, Robert Gray, deputy commissioner of the Orange County Department of Public Works, disputes that it is a risk or even a physical possibility, noting that the landfill is capped with a waterproof membrane and sloped to prevent precisely such a collapse.)  Just one week after our visit, however, the US General Accounting Office releases a report echoing Isseks' warning. Climate crisis-enhanced storms of the near-future pose a very real risk of catastrophic flooding at sites of toxic waste storage, the paper concludes, including several sites in New York State, along the Hudson River. The report also clearly states that it only addresses sites recognised by the US Environmental Protection Agency. The EPA "does not have quality information on the boundaries of non-federal" waste-disposal sites, such as those near Middletown; it does not know how many such sites there are, or whether they will be impacted by extreme weather events. They exist in a kind of environmental blind spot. "As I've started digitising some of this stuff," Isseks says, referring to his voluminous personal archives, including hundreds of pages of documents formally requested from Middletown administrators, "there's a sense that we're forgetting where the landfills are. We're forgetting where the poison is located. If nothing else, we've got to provide maps for the future, so that people know where not to build their houses or to dig their wells. This stuff is not going away. The problem will be relevant as long as it's here." Meanwhile, Middletown high school is rebuilding its media lab, although it is not clear what the focus of the students' work will be, or if they are even aware of their school's investigative pedigree. Isseks tells me that among city officials his students' watchdog role has been missed. With a mischievous grin, he relays a final anecdote. More than a year after the documentary was finished, Middletown politicians found themselves confronting yet another controversial project, this time a waste-to-ethanol plant. Orange County legislator Roberta Murphy wrote an exasperated letter to the local newspaper asking: where are those Middletown students, now that we really need them? • If you would like your comment on this piece to be considered for Weekend magazine's letters page, please email weekend@theguardian.com, including your name and address (not for publication). • This article was amended on 5 February 2020. Some text has been added or changed to clarify the locations of the landfills around Middletown. |

| Posted: 28 Feb 2020 10:30 PM PST ADVERTISEMENT MILWAUKEE JOURNAL SENTINEL Carter G. Woodson launched Negro History Week in 1926 as part of his life's work of shining a scholarly light on the neglected contributions of African-Americans to our society and culture. Today there are people who are uncomfortable with Black History Month, as we now call what Woodson started, for various reasons, including the perception that it can tend to limit appreciation of black accomplishments to the shortest month of the year. But there are still plenty of black artists whose work deserves wider recognition. We asked some of our cultural critics and arts writers for appreciations of performers and creators whose contributions to our culture are underappreciated or even unsung. While their choices have some fame in their fields, they're all creators who should have a wider audience. Serendipitously, the four the writers chose have a strong connection to the Caribbean islands, showing that immigration continues to be a freshening influence in the body of American culture. Harry Belafonte Harry Belafonte released an album simply called "Calypso'' in 1956. "Calypso" was nothing less than a revolution at 33 rpm. The album spent an incredible 31 weeks at the top of the Billboard album charts and is one of the most successful albums in Billboard history. It spawned two massive hit singles, "Jamaica Farewell" and "The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)," and the commercial impetus it gave to folk and world beat music continues to echo today. Characteristically, Belafonte refused to exploit the calypso craze and instead turned his attention to the wider spectrum of folk and world music including chain gang songs, blues, spirituals, lullabies, African, Greek and even Yiddish material. If anything, his influence grew. Bob Dylan made his national recording debut playing harmonica on Belafonte's album "Midnight Special." His 1959 double disc concert album "Belafonte at Carnegie Hall" spent three years on the charts and was the first live album to be a major commercial success. At the same time he was popularizing folk and world music, Belafonte was conquering live theater, films and television. In 1954 he had won a Tony for his work in the play "John Murray Anderson's Almanac." In 1957 he defied racial attitudes of the time when he appeared in "Island in the Sun" as a character who weighs whether to have a romance with a white woman. He was television's first black producer and won an Emmy for the special "Tonight with Harry Belafonte." In 1968, Belafonte found himself at the center of controversy when he appeared on a NBC television special hosted by British songstress Petula Clark. Clark touched Belafonte's arm briefly in the show, which led the sponsor Plymouth Motors to request the segment be cut. To her credit, Clark did not back down and the show aired intact to high viewership. As one would expect, Belafonte was and still is no stranger to controversy. He was a good friend of Martin Luther King Jr. and an active presence in the civil rights struggle. Belafonte also has a long record of humanitarian work. He was one of the main organizers of the "We Are the World" benefit for African relief in 1985 and also appeared in Live Aid. In 1987, UNICEF appointed him a goodwill ambassador. Even in his 80s, Belafonte remains outspoken and sometimes sharply critical. In 2006, he drew fire for referring to President Bush as "the greatest terrorist in the world." Earlier he clashed with the Bush administration when he referred to then-Secretary of State Colin Powell and Condoleezza Rice as house slaves for their high-ranking positions in the administration. It is, however, the music for which he will rightfully be remembered best.  RHONDA VANOVER/SOUTH FLORIDA SUN-SENTINEL Edwidge DanticatShe was only about 25 when her first novel, "Breath, Eyes, Memory," began casting a spell over readers in 1994. Critics praised Edwidge Danticat as a graceful and vibrant writer and forgave some of the excesses in this story of a 12-year-old who leaves her home in Haiti and moves to New York City. Four years later, Oprah Winfrey picked "Breath, Eyes, Memory" for her TV book club — and introduced its author to masses of readers. And though Danticat is known in literary circles, her complete works are worthy of wider recognition. At 37, she is still at the start of her career. If her work to date is any indication, she could grow into one of 21st-century American literature's major immigrant voices. Her novels and short stories deal frankly with the horrors of her native Haiti and of the inner struggles and losses of the exile, the immigrant. Her themes range from mother-daughter relationships to sex, migration and lives disrupted by history and the struggles of a post-colonial nation. Her emphasis so far has been on women, but male responses to a disrupted, uneasy history are also explored. "I struggle with horror myself, just the way things keep happening in our history," she told the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel during a 2004 book tour. "It is the reality of a generation of Haitians who grew up with a shadow of horror. I remember fear as a child, always: the fear of expatriate invasions, the fear of American invasion, a regime using everything — public executions — to stay in power. But because people had to, they went on with their lives, even with the horror all around. That's what I try to convey, that even with this horror, people are living their lives." "Breath, Eyes, Memory" explores that fear through a mother remembering being raped by the paramilitary group Tonton Macoutes as a child. "The Farming of Bones," Danticat's second novel, recounts a 1937 massacre in Haiti; it won the 1999 American Book Award among other awards. Danticat, who lives in Miami with her husband and daughter, was born in Port-au-Prince in 1969. When she was 2 her father left to look for work in New York. Two years later, her mother followed him, leaving Danticat with an aunt and uncle. Danticat grew up speaking French and Haitian Creole. It wasn't until she had moved to Brooklyn to join her parents at age 12 that she began to speak English — a late-blooming facility that now glows in the suppleness of her prose. She began writing fiction seriously in high school after the New Youth Connection published an essay she'd written on her immigrant experience. She went on to study French literature at Barnard College and earn a master of fine arts degree from Brown University. In 1995, the year after her first novel came out, she published "Krik? Krak!" a collection of stories that won her a nomination for the National Book Award. Danticat's second collection of stories, "The Dew Breaker," came out in 2004. It is a chilling yet moving exploration of Haitian lives both on the island and in America. (The title refers to government torturers who come to pick up their victims at dawn, breaking the dew on the grass.) Among her awards is a Pushcart Prize. GRANTA magazine named her among the best young American novelists in 1996. Danticat's "Brother, I'm Dying" was released by Knopf in 2007. Hazel ScottMCT "Play it, Hazel. Play 'As Time Goes By.'" Hey, it coulda happened. While the studio was in preproduction on what would become one of the greatest movies of all time, Warner Bros. executive producer Hal Wallis urged casting director Steve Trilling to check out a singer-pianist who was all the rage in New York. Forget that the script for "Casablanca" called for a black man to play the part of Rick Blaine's (Humphrey Bogart) piano-playing comrade; Hazel Scott "would be marvelous for the part," Wallis wrote Trilling in a February 1942 memo, quoted in Rudy Behlmer's studio history "Inside Warner Bros." That the studio stuck to its original plan — and gave singer Dooley Wilson a bit of movie immortality in the process, with "As Time Goes By" — was the first time Scott's star was dimmed. It wouldn't be the last. Born in Trinidad in 1920, Scott was a natural at the piano. Not long after she and her family immigrated to New York City, the 4-year-old Hazel climbed onto a piano and began playing a tune — in perfect pitch. She had her first recital at age 13; at 16, she was hosting her own radio show; at 18, she debuted on Broadway and was fronting her own band. But her star shone brightest on New York City's bustling nightclub scene. Scott's gigs at Café Society were the talk of the town. In 1945, Scott married Adam Clayton Powell Jr., a New York congressman and civil rights leader. Neither shied away from taking a public stand against racial injustice. When the Daughters of the American Revolution refused to allow her to perform in Washington's Constitution Hall, she and Powell made a federal case of it, leading to protests and calls for the group to lose its charter for its discriminatory policies. Scott landed appearances in a handful of movies. In the biggest of them, she plays herself in an extended scene in the 1945 George Gershwin biopic "Rhapsody in Blue." In July 1950, she became the first African-American to host her own television show. Then the roof caved in. The same year she made TV history, her name was included on a list of communist sympathizers. In an attempt to win back her reputation, she volunteered to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee; while her testimony drew praise, her concert bookings slowed to a trickle. Scott eventually moved to Paris, where her career revived, albeit out of sight of American audiences. After a decade, she returned to the States. This time, the adoring crowds were gone, but the artistry, and the pride, remained, jazz critic Leonard Feather recalled. Scott died in 1981 from pancreatic cancer.  DONNA WARD/ABACA Kool HercWithout the man born Clive Campbell in 1955 in Kingston, Jamaica, there would be no LL Cool J, no Jay-Z, no 2Pac. We never would have been urged to pump up the volume, to push it, to lean back or to get low. Beyond the world of hip-hop, without Campbell, acts from Beck to Moby, Korn to Britney Spears, would lack a crucial influence. Stages from Ozzfest to your average Euro-trash club would not sound the same. Campbell moved to the Bronx with his family in 1967. In 1973, the teenager began to play music at parties organized by his sister in the rec center of their apartment building. Disco was the ruling style of the day, but Campbell drew heavily from late '60s funk. And he did more than just spin the records. Working with equipment that seems Stone Age beside today's digital turntables, Campbell taught himself how to isolate a song's rhythmic spine — that pairing of percussion and bass known to cause visceral booty-shaking — and repeat it, over and over, switching from one turntable to another. Above his addictively danceable beats, Campbell often "toasted" — addressing specific people on the dance floor or pumping up the crowd with repetitive phrases. Ever been told to throw your hands in the air and wave 'em like you just don't care? Thank Campbell for importing the toast tradition from his native Jamaica. Kool Herc — his stage name evolved from the nickname "Hercules," after his muscular frame — began performing with two friends who favored microphones over turntables. The rappers' verbal acrobatics of rhyme and rhythm were the perfect compliment to Herc's increasingly complex turntable showmanship. Herc and the Herculoids were born, creating a template — two rappers and a DJ — that would give us Run-DMC, Salt 'n Pepa and a host of other hip-hop stars. As breakbeat-based music became a billion-dollar, global movement that would influence electronica, pop, alt-rock and nu-metal, the originator became a footnote. None of Herc's legendary, ground-breaking performances were recorded. And unlike many other old school pioneers, Herc has resisted the temptation to release a tossed together album for a quick buck. The real godfather of hip-hop still spins today, however, in the Bronx, at parties on both coasts and across Europe. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "famous short story,short stories for high school" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment