“Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine

“Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine |

- “Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine

- 100 books to read while stuck at home during the coronavirus crisis - USA TODAY

- HISTORY: Elizabeth Borton de Treviño: Building Cultural Bridges Through Literature - The Bakersfield Californian

- The seemingly perfect world of author Clarissa Goenawan - The Japan Times

- All the celebrities who have shows or movies coming to the new short-form streaming platform Quibi - Insider - INSIDER

| “Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine Posted: 28 Mar 2020 06:00 AM PDT Janina Romero Each month, Future Tense Fiction—a series of short stories from Future Tense and Arizona State University's Center for Science and the Imagination about how technology and science will change our lives—publishes a story on a theme. The theme for January–March 2020: politics. Translated by Will Vanderhyden.

1. What's Left of the WorldI was born in a distant time, when vanilla ice cream was yellow. The world had agreed it should be that color, but later in the 21st century it was changed to red. They say more is consumed now. People want red things. Dr. Fong is an herbalism aficionado. He concocts a vanilla extract the color of coffee. I asked if he'd ever considered dying it red. "Reality fakes colors, no need for us to," he said. I go visit him every three days to play chess. There's little to do under the violet clouds of Ciudad Zapata. The air here has a particular density; every morning I clean a film of dust off my desk. Those particles come from infinite waste. I thought it'd give me vertigo to imagine all the things and all the people who become the powder I wipe off my desk (what's left of the world), but the real surprise was that I feel nothing. At 91 years, habit is my medicine. Fong has asked me to write. To tell a story, knowing stories are no longer told. I've lived long enough to bear witness to the loss of my occupation, not an uncommon experience in the end. (My father worked at a printing press and my grandfather was a telegraph operator.) In 2020, three decades ago, I took a taxi. The driver asked me what I did for a living and didn't understand my answer. "Literature?!" he exclaimed. At the time, it struck me as ignorant; now I know it was prophetic. Old people are athletes; every movement is an extreme sport for us. If I spend half an hour in a chair, I know what'll happen to me when I stand up: pain in every joint. I have to go to the bathroom all the time. I'm so conditioned by the pain that just the idea of walking makes my knees hurt. People who play sports through injuries know the feeling: They're old in anticipation. Transitioning from stillness to movement is hard for me, but I can still walk the kilometer that separates my bungalow from the Processing Office. The route is safe. They no longer publish crime statistics. We intuit them based on increases or decreases in private militias. The guards greet me on my way to Fong's studio, raising a fist, encouraging an old man's marathon. Some belonged to previous outfits and use a mix of uniforms, like soccer players swapping jerseys. At the entrance to the Office, there's a metal detector, not particularly effective in the era of refined polymers. I set it off with my artificial hips and maybe even with my teeth; they contain more metals than the guards' service weapons. I leave home at 4, prime time for the heat of the machines to swathe me like cotton, relieving the cold in my hands. I make sure to return home before the neon ideograms light up and the scattered lamentations of mariachis animating the Chinese cantinas fill the air. Migrants are coming to Ciudad Zapata in search of work. By day, they grow like shadowy and wandering silhouettes. By night, they sleep on the esplanade under the open sky. On my way home, I see that horizontal nightmare: bodies stretched out like the corpses from a cataclysm. Not even the rain drives them away. They wait, and sometimes die out there, as if persistence would grant them rights. On the hottest days, when the wind blows toward my bungalow, an unmistakable aroma reaches me, the bitter odor of poverty. This is uncomfortable, but doesn't alter my habits (my medicine). Fong doesn't complain about this country either. He was dispatched here to take charge of the vast waste zone, after previously working in Southeast Asia and South America, heading up projects another kind of person would've been more boastful about. Despite his discretion, I know he graduated with honors in the field of zoonosis. The genetic modification of mosquitos eradicated malaria and other diseases, but increased the populations of animals that infect people. Fong was responsible for the cordons sanitaires that protected them from new swine and monkey viruses. He calls that time, which others might describe as heroic, "the time of the hecatomb," specifying that "hecatomb" refers to the ritual sacrifice of 100 oxen. While attacking my king in a game of chess, he talks about the millions of animals sacrificed so people could live. "Destroying trash is more relaxing work," he says, smiling. He talks about his country with statistical reverence and offers data on famines, deaths, and epidemics. He doesn't suffer nostalgia: He never goes to Swallow's Nest, Lucky Star, or the other restaurants that cater to the Chinese community. His cozy studio is furnished with Western antiquities: two rocking chairs, a coat rack, a piece of furniture with small drawers that once served as a reliquary in a church, threadbare rugs of complex fabrics. The room is presided over by a copy of Hieronymus Bosch's The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. I admire that elaborate fantasy, but prefer to sit with my back to it. The window looks out on a greenhouse where Fong grows orchids. The greenhouse's glass panes, of an extreme thickness, protect from the flashes and temperature fluctuations on the outside, where trash is slowly being transformed into energy. Rumors are necessary for maintaining order. Once, I went into Fong's work area, quite different from his private quarters. His assistant (whose name I don't know, but whom I call Chucho without any protest from him) is proud of his "programmable matter" device. He needs only to press a button to transform a cellphone into a laptop. Dr. Fong took the time to explain to me that this transfiguration is possible because the device's network of catoms (claytronic + atom) alters its programming and takes on other functions. The metamorphosis seemed both brilliant and unnecessary, conceived of for Chucho's entertainment (like turning a frog into a rabbit). Moore's Law, formulated way back in 1965, predicted the power of computers would double every two years, and then came the quantum expansion. Technology has created increasingly inscrutable gadgets, but Chucho will always be Chucho: If he presses a button, he expects a surprise. After showing me the "programmable matter," Fong asked, "What're you doing Sunday?" "Nothing," I said, which wasn't true. (I was supposed to go with Ling to the boring warehouse where she returns the goods that she purchases remotely but turn out to be different from the holograms promoting them.) The odd thing about the conversation was that Fong thought Sunday existed. It's hard to believe he ever takes a day off. I've heard rumors about the corruption of the Chinese managers. Back when I was still interested in ideology, I understood that their global supremacy depended on combining the defects of communism with the defects of capitalism. Later, I came to accept it as a natural product of the food chain. Someone has to take the last bite and I'd rather it be the Chinese, who in a way have saved us. Rumors are necessary for maintaining order, which Fong loves so much. The illusion of crime—the idea somebody might still commit one—is reassuring, because it's nothing but fantasy. Discussing corruption satisfies the residual longing for disorder that still lives on in thinking predators. Crime has become an unrealizable possibility and only takes place on a conjectural plane. I know this now, but shouldn't get ahead of myself in the story.

2. Lead, Carbon, SiliconeThat Sunday, I went outside the city with Fong. He came to pick me up in one of those customized trucks, outfitted with lead armor plating, which became popular when attacks were frequent and the Law of Transportation reduced the speed limit to 30 kilometers per hour. Fong pointed at the hood: "The lead protected against bullets and now protects against radiation. It's one of my favorite elements." This raised a question I couldn't ask anybody else: "What element do you mistrust?" "Silicone, of course! It's too common, the second most abundant element after oxygen. Transistors and transformers exist because of silicone. It's the new clay, 'programmable matter.' If a religion were invented today, God would mold people out of silicone." From there, we moved on to the I Ching. The doctor spoke of oracular mutations until he remembered the subject had arisen from silicone: "Imaginary transformations are good and real ones are acceptable. Transformations that are too real are the real problem." "How can something be too real?" "When it can no longer be imagined." "I don't understand." "You will." "At 91 years old, my expectations of learning anything are low." "Don't throw in the towel, professor," he smiled. We continued slowly on our way. In my old age, I've achieved leisure without being freed from anxiety. I hate the slow machinery of the new vehicles. Fong, on the other hand, adapts to every circumstance. I don't know if it's because he suppresses his reactions with furious discipline or if he's in possession of a fluid temperament that prevents distress. The truth is, I've never heard him complain. Because of the rains and the total lack of maintenance, the highway has holes the size of craters; in one, some vultures picked at an animal carcass. We slowed down and a group of half-naked children surrounded us to ask for spare change. Their teeth were brown from the chemical waste that leached into the water tables. Fong lowered the window and tossed them a bag of Chinese candy, with a calm expression, like a godfather throwing coins after a baptism. I was flattered Dr. Fong sought out my company. The man who runs the world's largest waste emporium is interested in me. Old age destroys one's prostate or ovaries, never one's vanity. We passed scraggly garden plots and little stores that popped up between trash dumps, until we came to something resembling a town: small colored houses, a wire arch that in another time held up brightly colored streamers of papel picado, a hammock store, a stand selling plants, maybe fruit trees. The asphalt blended with the gravel until we came to a basketball court. The backboards advertised a vanished soft drink brand and the baskets had no nets. In the middle of the court was a table. Four of the half-dozen chairs were occupied. We left the car in the shade of a laurel with leaves the color of mustard and walked to the two chairs reserved for us. "Welcome to the playground of the world!" the oldest one—quite a bit younger than me—said. "It's a pleasure to see a man of sound mind." That was the courteous way he referred to my age. "The years pass, but the game never changes: One hoop leads to day, the other leads to night; one to woman, the other to man, the eternal dualities. You wrote an article about that." "Centuries ago," I smiled. "You didn't bring a hat?" a woman asked me. We were out in full sun. Fong was wearing a palm hat. A man handed me a cap promoting a vanished political party. "I'd rather get sunstroke," I said, with a touch of my useless childish indignation. "The heat is the fault of the Chinese," another woman joked. This was true: The processing plants have increased the ambient temperature by 5 degrees (a wonderful thing, when you're 91 years old). They gave me a hat somebody else had already been wearing. I felt the sweat of another touching my forehead, but didn't take it off. Fong explained that these people were delegates of the Indigenous Council with whom he addressed "problems in the sector." From beginning to end, the delegates (two women and two men) carried the conversation. At one point, Fong wanted to change the subject and they asked him to respect the Agenda. He acquiesced, motivated by a deep respect or his military training. I didn't know what kind of representation our interlocutors had. I assumed the "council" to which they belonged was nothing more than an imaginary group or a guild. It bothered me when they compared the Founding Hero to a landowner who treated the country as if it were his own estate, but above all I was alarmed they thought I agreed with them. (One even suggested we'd met before.) I wanted to leave, but Fong took me by the arm. The Founding Hero has been governing so long it's no longer worth tracking the time ("I'll remain as long as the people ask," is his slogan). At his long rallies, he doesn't fall into the banality of referring to his enemies as evil. He calls them "reckless," "irrelevant," "lunatics," "egomaniacs," "chancers." This last insult is my favorite; it refers to those ne'er-do-wells who live off the opportunities offered by the State. I've resigned myself to being a chancer. On the basketball court, presented as the "playground of the world," I felt I was in the company of the Founding Hero's true adversaries. The fear of being caught with them only increased when they attempted to calm me: "We're in a valley and the stone contains a lot of minerals: Carbon doesn't transmit here." My anxiety didn't fail to comply with the norms of biosecurity, because I couldn't be detected. That worried me more. I was forming part of an operation. Why had Fong led me into that ambush? One of the women took out an old newspaper clipping. Despite the fading print, I saw my own face. "You used to be with us," she said. The Founding Hero has been governing so long it's no longer worth tracking the time. I couldn't make out the scene (a public plaza in an unrecognizable city), but a sensory confusion overcame me. Thirty years ago, I participated in activities I've managed to forget. In that naïve time, ethnicity was all the rage. The most diverse objects were decorated with indigenous motifs. Slippers, folders, plastic boxes, cellphone protectors, pajamas, jackets, paper napkins, tablecloths, swimming suits, and towels alluded to Antillean, Inuit, African, or Mesoamerican (taken together, they seemed to emulate peoples of Oceania) ethnicities. Lip service was profusely paid to the original peoples, pushed off their tribal lands. It only served to increase the varieties of indigenous-inspired wallpaper and allowed the Founding Hero to promote his Progressive Development Plan. What'd I been doing at that time? I didn't want to remember. Fong intervened. He said that the Chinese and Mesoamerican civilizations had known such splendor that could only now be recovered through legend; in Beijing or Mexico City the present would never be as strong as the past. As an expert in zoonosis, he remembered that our countries broke news with infections (the swine flu of 2009 and the coronavirus of 2020). "They take us into account when we get infected," Fong said. "The people most resistant to threats are the ones who have suffered the most because of them," referring to our host, presumably, but also to the thousands of Chinese who had lived invisibly in Mexico, on the margins of documentation and statistics. When it was created, the Ministry of Biosecurity had no reliable data on the Chinese or the indigenous peoples. Even today, they remain a dark zone, of little interest to the Founding Hero, because of their minority status (he limits himself to reiterating the number of his millions of supporters). I noticed that Fong was only speaking to me. The rest of them were already aware of what he was saying and listened impassively, which alarmed me: "The alliance among undocumented people must have taken place long ago, but the Chinese immigrants were devoted to their small shops, using passports of dead people, and the indigenous people were displaced from their lands. When I arrived here, several years ago now, I suspected there were immigrants among the plant employees. They were whimsical and distracted, but they pretended to be disciplined. The enigma of their behavior intrigued me and I didn't report them. When I met the people from the Indigenous Council, I knew they'd also escaped the Ministry of Biosecurity's carbon chips." He adopted the detached tone he used when getting sidetracked during our tea and chess sessions: "After combating epidemics, I became interested in a possibility: choosing my own disease." As he spoke, he softly tapped the table, as if it were a keyboard. One of the women imitated him. It was as if they were communicating in Morse code. Fong smiled seeing how her gesture coincided with his own: "I don't belong among the old immigrants: I'm Chinese from China," he brought two fingers to his head, a signal that he had carbon conductors implanted there, "but we didn't come here to talk about this." They handed me a document that explained my presence there. They wanted me to review the wording. I read an archaic message about the rights of the original peoples riddled with the word hope. The wording seemed correct to me; I only had to cut words that had fallen into disuse and adjust the punctuation, which I found rushed. "We learn from our mistakes." With those words from the doctor, my corrections were approved. The others thanked me and gave me a weaving, with the image of a smiling sun embroidered on it. The air smelled of roasted corn. The meeting wrapped up quickly and I feared they wouldn't give us anything to eat. But they gave us some tamales for the road. Fong was kind enough to give me his. I ate the luscious masa as if returning to my childhood. I found the concept of "a man of sound mind" flattering, but applied to me it could only be ironic. One scene summed up our trip: When I handed back the corrected document, Fong gave me the same soft smile I'd seen him give his "programmable matter." My encounter with the indigenous council had been a test.

3. Green TeaI came to Ciudad Zapata after my third retirement. Cuts in the cultural sector had forced me to accumulate three pensions. After decades of writing for a journal that achieved the artisanal glory of being printed, for a news agency, and for a state-run publishing house, I was able to retire. Obviously, it would've all been far simpler if I hadn't been married three times. With the current laws, even moving to Venus won't save you from paying alimony. But I can't complain: Ling accompanies me with the shifting constancy of the phases of the moon. Though she's here with me, she comes and goes. There's little physical contact between us, apart from when she puts the Stygian drops in my eyes, to lengthen my life or maybe preserve my eyesight. When she stands up from the table or says goodbye, she touches me with distracted tenderness. That's not what keeps me by her side. Our lives crossed like two contrails in the sky. I've been captivated by this phenomenon multiple times: One white slipstream begins to dissolve overhead as another passes through it, giving it new meaning. Why did Ling decide to stay with me (it would be sad to say "accept")? She's among the 90 percent of women who aren't granted fertility authorization. Having a young partner wouldn't provide her the benefits of procreation. Relationships have been devalued. Tellingly, they are considering building the primary penal colony on Venus, the ancient planet of love. Ling likes young men with beards. She goes out with them until the night they start crying hysterically. "Pretty boys are weak," she says, with the serenity of someone speaking to a man too old to care about being ugly. For me, libido is a pleasant variation on the theory. I imagine Ling's erotic encounters without losing any affection for her. We coexist in a harmony only people who expect little from each other can attain. Ling arrived with the founders of Ciudad Zapata. She and I met in the capital, at my last job, which no longer paid out any pension. In 2030, at 73 years old, I was a teacher of Linguistic Normalization. My students had come to Mexico along with the global trash crisis. For decades, China bought trash from the United States and processed it within its own borders. Social demands and sanitary emergencies made it so impossible for China to continue absorbing such a vast quantity of waste. (Laid out flat, it would have covered the entire surface of Australia.) A new space was needed for all that trash, preferably somewhere near the United States. And so, to that end, the Founding Hero offered up the states of Michoacán, Guerrero, Jalisco, Nayarit, and Colima. The chancers said the Pacific coast would become a landfill for hire, but the Founding Hero had an additional agenda: finally cracking down on organized crime in the region. The drug cartels who controlled the area were pushed out by Chinese-backed occupation forces sent from the capital, to make way for a far greater business: the trash of the world. Ling took my Basic Spanish class. The Founding Hero claims everything can be said with the meager vocabulary he deploys at his rallies. Literary genres have disappeared or become hermetic. In a strict sense, this story is written in code. I miss literature, but I must admit that Ling's limited range of phrases eliminates emotional issues. Sometimes she has a random poetic impulse. She spoke to me of the shadows lengthening under the red sky of Ciudad Zapata, where trash burns 24 hours a day: "I would like to see your shadow there." Romantic advances in the workplace are frowned upon. I hadn't made the slightest attempt to approach Ling; six decades and thousands of words separated us. I admired her flowing hair and silky silhouette with the removed perspective of someone staring at a sunset. But Ling saw something in the few words I taught her. She spoke of my shadow and I quit my job to go with her. Her family had arrived in Mexico with the Tlaltecuhtli Project. The Founding Hero decided to honor the Aztec goddess who devours corpses while giving birth—the perfect symbol for recycling—but the name turned out to be unpronounceable for the Chinese. And so the main plant and accompanying buildings were christened Ciudad Zapata. I remember the photographs that spun around the mediasphere: the Founding Hero and the Chinese head of state breaking bread at a banquet where they served red—the new color of vanilla—ice cream. The lifeless streets of the city-plant bored me. The U.N., which is devoted to the harvesting of amusing data, claims Mexico is one the few countries where street dogs are still prevalent. None of them are in Ciudad Zapata. I appreciated the purr of the engines processing the waste, the red sunsets, the faint chemical odor that hangs in the air, but I understood why the Chinese took refuge in tequila and sad ranchera songs. Dr. Fong is Ling's great uncle. She took me to see him to give me something to do. She left us alone, as if we should have been celebrating an agreement. I thought the doctor would criticize me for sharing my life with a woman six decades my junior, and in a way he did. He quoted Confucius: "Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves." He had cause to object but no desire to resort to it. Our friendship sprang out of that avoided dispute. Fong is a biologist, specializing in zoonosis, but his training also includes crystallography, digital programming, linguistics, and ecology. In his country, he has a military rank. He operates with the methodology of someone who knows how many pills are left in his bottle of painkillers. (I put it to the test once when I had a headache and it didn't surprise me he knew the number.) Even in his hobbies, he acts like an expert: He lets me play with white, but always wins our games of chess. He masters Spanish with old-school rigor. I asked him what he thought about the Founding Hero calling the country the "nursery of recycling" and he said, "I've spent a great deal of time in the dangerous company of geologists: We've wiped out flora that's been around for 85 million years." It would've surprised me if he contradicted the Founding Hero. He didn't, but I was struck by the adjective dangerous being applied to geologists. The green tea Fong drank had a strange aftertaste. At first, I was afraid it was a diuretic and would force me to painfully get up to go to the bathroom. The odd thing was its smell and consistency, slightly mossy. For decades I drank coffee with the desperation of someone who needs energy to pay alimony. I know little about tea, but even I could tell there was something special in that substance. I didn't dare mention it during our first encounters. I put off my question until it became a secret. Once my visits had become routine, I got up the nerve to broach the subject. Fong answered: "The tea has rue leaves in it. Do you remember Pedro Páramo? The protagonist keeps a portrait of his mother in the company of some rue leaves. Rulfo knew what he was talking about: Rue combats the 'evil eye.' " I don't know if Fong really talked like that or if the tea helped me hear him that way. He continued his explanation: "This has a scientific basis: rue—Ruta graveolens, also known as 'herb-of-grace'—gives off a powerful electric charge and combats ills attributed to curses and extreme ennui. [He paused, took a long sip, and I thought maybe he was drinking another kind of tea.] It also affects carbon atoms," he added. There was nothing more to add. I was dumbfounded and he took advantage to take my picture. The lens looked to me like the eye of a cyclops or minotaur as Fong smiled: "I'll store your portrait with some rue leaves." "Where do you get the plants?" "From the people you met on the basketball court." He walked, with enviable agility for an 82-year-old man, to the wall that ran adjacent to the window. He pulled back a curtain, revealing a painting made of colored yarn. I could see asterisks, spirals, the antlers and eyes of deer. "Beautiful, right? Huichol art," Fong said. "The most interesting thing is that it worked for a healing. A patient was cured by looking at it." His voice quavered on those final words. I thought I understood that he was that patient. "What happens with the carbon?" I asked. "What happens with the carbon?" I asked. "There are things I should tell you and things you should think over on your own." Though his words had an oracular solemnity, I found them amusing. I had become Fong's disciple. The superiority with which he treated me made me feel younger. My eyes moved to The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. It struck me that I wasn't there only because the doctor wanted to beat me at chess. "It's getting dark; you should head home to be on the safe side," he said. The tea had given me a boost. On my way home, the neon ideograms shone brighter and my breathing came easy. Ling wasn't home. I thought about the dive bar where they served booze in candleholder glasses and she hooked up with hysterical men. She took me there once so I would be familiar enough with the place to imagine it. In the back, some colored spotlights formed a Virgin of Guadalupe. At the time, it didn't bother me; now, remembering it, it seems insufferable. The tea was making me feel an uncomfortable vitality. Two or three days later, I looked through her bag when she was in the bathroom. In the case where she stored interchangeable chips, I found the photograph Fong had taken of me. I was surprised she had it. Did she hang onto it out of genuine interest, out of superstition, out of the almost-forgotten custom of making a connection? Ling can't see me how I see myself. I cherished the two moles at the base of her neck and the whitish scar, the size of a grain of rice, that graces her wrist. At night, she stared at me for a long time, as if trying to compare me to the photograph, or imagine me some other way.

4. The ExperimentOne afternoon I went to see Fong and as always we played chess. I remember I had a knight in my hand, it slipped from my fingers, and I suddenly passed out. I came to in a nondescript room, under an irritating light. I looked away and felt pain in my neck. I saw Chucho. Though I didn't hold him in high regard, it was a comfort to find him there. His round silhouette and mild demeanor didn't pose a threat. I saw him touch a portable screen with his fingertips, in a focused, efficient way. Had I suffered an attack? At my age, any fall has consequences. Would I ever walk again? "Chu-cho … " It embarrassed me to call him that, but it was already too late to learn his true name. He came over right away, with a small metal cup: "Water." He helped me sit up. Dr. Fong arrived immediately thereafter, with his enviable light step. He said something to Chucho (he did so in Chinese and I had no idea which of the words he spoke was Chucho's real name), who immediately left the room. Fong sat down beside me: "My assistant is phobic, he can't bear physical contact, but there's no one I trust more to take care of you. How are you?" I felt a mild dizziness and a buzzing in my left ear. I told him so. "It's normal. It'll soon pass. You were in the care of the Indigenous Council for several days." "How long?" "Long enough to finish the treatment. Do you remember it?" "Nothing. Where are we?" "In a safehouse. There's metal in the walls. Electricity from outside can't get in. A true 'Faraday cage,' but I suspect that means nothing to you." "You suspect correctly." In my pocket, I discovered a weaving. It was embroidered with a smiling full moon. It was the complement to the shining sun weaving they'd given me on the basketball court. I remembered what they'd said about dualities on the "playground of the world." The thousand-year-old game of pelota still retained its symbolic meaning. I brought the weaving to my nose. I breathed in the smell of lost fruits, the tremolo of a violin, the faraway touch of a hand. That day, the four indigenous representatives had touched my fingers in a timid way. And yet, I felt how manual labor had softened their palms and left callouses on their fingers. Instinctively, I knew those were the hands that'd cared for me while I was unconscious. With sedulous patience, Dr. Fong told me what had happened. I listened with bewilderment, then with fear—and at last, with the irritated acquiescence with which you accept the inevitable. "Write what happened," he said. It wasn't a suggestion, but an order delivered in a kindly tone. He left the room and came back with a notebook and pen. I don't know how much time I spent in that windowless room. In the back, there was a bathroom with no shower. They brought me meals three times a day, but I stopped keeping track. Fong visited to review information or fill in lapses in the narration. Chucho accompanied me in silence, sunk into his screen. His hypnotic focus led me to believe he had a slight mental disability. In those days I learned that his apparent dullness was the result of a very high degree of specialization. He was creating complex algorithms, according to Fong. The most recent had to do with me. It isn't easy to narrate an autobiographical story someone else recounted for me. "That's part of the experiment," Fong said. "If you tell it well, it'll cease to be an experiment: A successful experiment isn't experimental." I had to overcome the indignation of being in captivity. At 91 years old, I wasn't interested in surrendering my dignity. I merely wanted to see Ling again and my safe passage was the story Fong had asked of me. It all began when she suggested I go to Ciudad Zapata. What she did wasn't a coincidence. For a moment, I gave into the vanity of thinking she'd researched me of her own accord. I guess between her, her uncle, Chucho's computer, and the long memory of the indigenous people, they were able to reconstruct my old activities, my axed occupation, the disordered romantic biography that made me easy prey. I hated having been used. A lingering trace of pride made me believe Ling couldn't have been totally indifferent toward me. The discipline with which she carried out her mission might not be incompatible with taking pleasure in it. I got distracted thinking about this and Fong asked me to focus. With unfeeling objectivity he added, "Experimenting with someone your age is less risky than with a younger person." If the experiment failed, it wouldn't ruin a life, just accelerate a death. If the experiment failed, it wouldn't ruin a life, just accelerate a death. His words conjured confusing images. As he retold it, his story slowly became memories. So were those memories real or induced? In a vague way, like someone looking at out-of-focus realities, I supposed they were mine. Just as I did so, I felt a shiver from another time. After drinking tea in his study, I'd suffered a blackout. I was taken to the village where the representatives of the Indigenous Council interviewed me. Though Fong didn't reveal what herbalism practices I was submitted to, I guessed rue leaves played a role in the disconnection and reconnection of my cerebral circuitry. Since the Founding Hero created the Ministry of Biosecurity, ECOG technology is required to get enrolled in the National Census. Nobody was frightened by having carbon sensors that produce electrocardiograms implanted in them. Locating them is simple, but the cerebral cortex assimilates them in such a way that removing them becomes exceedingly complex. It would've never occurred to me to remove my sensors. I thought about The Extraction of the Stone of Madness in the doctor's studio, and the painting struck me as subversive. The carbon nanoconductors allow us to listen to the Founding Hero's rallies, but most importantly they record our thoughts, habits, and tendencies. It's more what they transmit than what they receive. In a distant time, personal data was gleaned from our cellphones and computers. Today, social DNA is extracted from the source, our brains, a fact both well known and unimportant, because the electrocardiograms create stable patterns of acceptance. It shocks no one. The brain is a transaction. As Fong spoke, Chucho worked on his screen. At some point, the doctor spoke about decision-making. For decades, neurophysiologists had known it wasn't dependent on will, but on electrical impulses: "The brain takes note of the decision after making it." If you control personal information, it's easy to lead people to what they supposedly want. Chucho created algorithms that offered progressively reduced "options." That activity had a paradoxically liberating effect: It saved you from free will. "Choosing is a terrible burden," Fong said, then he added: "The Founding Hero doesn't impose his control: The people conform to the monotony of supporting him. These have been the 'Decades of Happiness,' as he says. The only nonconforming messages are the ones in fortune cookies," he smiled, "because they suggest the possibility of greater happiness. The Founding Hero talks about the chancers and other adversaries so we'll believe that resistance is still possible." He took the screen from Chucho's hands and showed me an incomprehensible diagram: "The 'decisions' you've made in the last 30 years." The graphic seemed sad to me. "You made no mistakes: a model citizen," Fong said, as if he were talking about a silicone mold, one that really disappointed him. Then I remembered that Ling had detected an anomaly in me. During one class, I talked about when vanilla ice cream was yellow. My nostalgia caught her attention. I wasn't demonstrating nonconformity, but I'd remembered something outside the record: a color from another time.

5. The Disorder of the TruthI came to understand the meeting with the indigenous representatives in a different way. They didn't need a copy editor. The motive for the meeting had been something else. They submitted me to a test, offering me the cap of the old political party: The sensors didn't work in that mineral-covered gully and I demonstrated my repudiation. Then they gave me a sombrero with traces of someone else's sweat and I used it without protest. That inspired trust. They handed me an old document; I cut words and adjusted punctuation. Fong paused as he reached this point in our shared story: "What changes most in a writer's work is punctuation; that's where the signs of maturity or old age lie. Who do you think wrote that original text?" An emptiness opened up in my stomach as I recalled the moment I came up with those ideas about justice, the recovery of tribal lands, hope defended from the grassroots. That text came out of an unreal time (2017?) when there were still elections and activism was possible. At the time, I participated in a failed campaign for an indigenous candidate. They hadn't forgotten it. The herbs did their work during the days when I was sedated or awake but unable to remember it. My carbon sensors had been blocked. "You're the first patient of a new illness," Fong said, as if it were good news. He went over to a screen and what happened was terrible. For years, I had heard the Founding Hero's words the way you hear distant murmurs, waves in the sea, buzzing engines, rain falling on the glass of a greenhouse. The image I saw on the screen seemed recent, but the origin of those words was remote and precise: I had written them. I remembered being in the office where I served my sentence for being a "failed writer" (forgive me the well-known pleonasm). By night, I wrote texts that were deemed subversive; by day, I composed pompous speeches so the Founding Hero could say the same thing without consequences. My nocturnal writing was a protest against the uselessness of my daytime writing. I was in the service of both the rebellion and the demagogy. I was a critic of power, but helped perpetuate it writing formulas that banalized radicality. "You've got to make a living somehow," friends familiar with my work as ghostwriter said sarcastically. The worst part was that my motives weren't strictly financial. I actually thought the indigenous people would never achieve change from below. I wanted to influence the government's peaceful reforms and was awaiting my moment of vainglory: The Founding Hero, who listened to no one, would listen to me. Was it worth it to belatedly remember this error? I hated that Fong was submitting me to this torture and I asked him to leave me in peace. "At 91 years old, you can still start something," he teased my vanity. "There's injustice and violence, but nobody cares. People live in satisfied submission," and with the severity with which he moved a bishop on the chessboard, he added: "Submission is an algorithm. That's why we decided to infect you; error is your cure." I hated that I'd drank his tea. Reality laid bare not only seemed unbearable: I had helped create it. "And you, what do you gain?" At last I asked the decisive question. Maybe he was thinking of Confucius when he said: "I don't want revenge. I work with the greatest wealth on the planet: trash, human waste. An increasing number of the world's bodies end up here. The United States never realized that when they entrusted China with the control of their waste. We extract the nanoconductors with personal data on them and turn the bodies to ash. We keep the information. We have the greatest repository of human data in history, something colossal, don't you think? Every civilization is known by its funeral rites," he paused. "Coincidence brought me here. My country agreed to sully itself with foreign waste and your country resigned itself to being waste, but maybe it's not too late to change things a little. Write, my friend, write your story." "Nobody reads stories anymore." "Take a risk: We can't forget the future." "Things that cause us pain are of great value." He explained how patients suffering amnesia can't guess what will happen the next day. Eliminating the past prevents projecting into the future. As a patient, I was the opposite. I was engaging in an archaic practice that helped to imagine what was to come. I remembered the Huichol painting in his studio and the way he pulled back the curtain to reveal it. "A patient was cured by looking at it," he'd said. I asked him about it. "I hoped we would come to this. When we were building the plant, I suffered an accident. The place where the engines now rumble was an infinite garden, a branch of paradise. It was sad to see how the excavators destroyed the gardens. The destruction of thousands of fruit trees filled the air with the smell of citrus, sludge, and gasoline. Someone told me there were still orange trees on one hill and I went there. I wanted to see something that would be lost forever. I was so relaxed I didn't notice a drop and I fell over a cliff. I was rescued by the indigenous people you met on the basketball court. They saved my life, but also made me drink herbal infusions that gave me back the singularity, the defects I'd suppressed. We learn from our mistakes, as I said already. We have to save that: the 'human factor.' " "So, I'm not the first patient, you are." "In a certain way I was. I was delirious for days, in front of the painting that's now in my studio, thinking those arabesques were reality, until I realized they represented the poison I'd sucked out of reality. The interesting thing is it's a beautiful poison. Things that cause us pain are of great value. It doesn't matter who Patient Zero is. You must write your story. Don't worry about the errors: We depend on them. You've had a long life; you can write with the perspective of a person who has passed through many modes of punctuation." "And you?" "I don't tell stories, my friend. My errors are technical; yours are of another kind. Write: Make mistakes. Avoid qualification: Error is invaluable." For a moment, I feared Fong wanted to incriminate me with my confession, but I believe he had other motives. I need to believe it. His rebellion has a scientific basis. I know how he plays chess: For him, the rules are useful if they provide a stimulus. Now he is seeking other rules for dealing with reality. Maybe Chucho is designing a diagram that summarizes the complex network of resistance that's thriving among the original peoples, the old Chinese immigrants, and those individuals who alter their carbon conductors and return to a contradictory reality, thanks to almost-forgotten herbs, the tea of thick consistency I drank in Fong's company. I've convinced myself he drinks the same substance. I want to believe the clandestine work he carries out while grinding up tons of waste obeys a principal that until recently would've seemed illogical to me: He saved millions from the animal contagion in the "times of the hecatomb" and now he's taken on the greater challenge of saving us from ourselves. My own motives are clear: I long for uncertainty, what in previous times was called "literature." I supposed Fong will include these pages in the data collected from the trash. I don't know the scope of his strategy, because I've only been its tool. It comforts me to know that my contribution wasn't entirely imposed on me, that I was guided by a personal conviction. A woman took interest in me because I spoke of the bygone color of vanilla. I remembered that before leaving for the chess game when I lost consciousness, I ran into Ling in the kitchen of the bungalow. When she saw me, she hurriedly put something away. We talked for a while and then she went to her room. On the table I saw scraps of tea leaves. I brought them to my nose and breathed in the smell of the substance Dr. Fong has been giving me. Ling also sought irregularity. I see her silhouette, outlined against the dense and reddish sky of Ciudad Zapata, and imagine a future for her, a future I'll never see: Ling reads this line and understands; she accepts the disorder of the truth (the exception and the error); she finds a way to feel and, maybe, to love. Read a response essay from Adam Minter, author of Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade. More From Future Tense Fiction And read 14 more Future Tense Fiction tales in our anthology, Future Tense Fiction: Stories of Tomorrow. Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society. |

| 100 books to read while stuck at home during the coronavirus crisis - USA TODAY Posted: 28 Mar 2020 06:00 AM PDT — Recommendations are independently chosen by Reviewed's editors. Purchases you make through our links may earn us a commission. Our colleagues Barbara VanDenburgh and Mary Cadden from the USA TODAY Life team are here to share book recommendations to get you through social distancing. Every year, you make the same New Year's resolution. No, not the one about losing weight – the one about reading more books. And every year, you mean it. Maybe you join a book club, even if just virtually with Reese Witherspoon and Jenna Bush Hager. But that well-intentioned to-be-read pile of books on your nightstand just gathers dust. Well, now that ther coronavirus pandemic has us all social distancing in our homes like hermits, we know for a fact that you've finally got all the time in the world to read. That latest best-seller you've been itching to devour? That rom-com you hope you're dying to fall in love with? Heck, even that copy of "War and Peace" you've had since you were feeling ambitious in college? Now's your chance. In case you need a little inspiration, we've compiled this list of 100 book recommendations covering all the bases. Happy reading. Celebrity memoirs"Face It," by Debbie Harry: Sex, drugs and rock 'n' roll: The Blondie singer tells about it all in her revealing memoir. ($28.59 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "In Pieces," by Sally Field: This brutally honest, bracing account of Field's life takes on difficult topics, including the sexual abuse she says she suffered as a childat the hands of her stepfather. ($25.52 hardcover or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Me," by Elton John: The music icon tells his story for the first time in an intimate autobiography, charting the stumbles and triumphs on his path to enduring superstardom. ($26.40 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Brother & Sister," by Diane Keaton: The Oscar-winning actress examines her upbringing with her only brother, Randy Hall, and tries to make sense of how their paths diverged and why he led "a life lived on the other side of normal." ($22.83 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Inside Out," by Demi Moore: The famed actress charts her life from the insecurities of her childhood, through addiction and skyrocketing fame, to motherhood and marriages. Her story is equal parts adversity and resilience, told with candor. ($24.63 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Becoming," by Michelle Obama: The former first lady shares stories from her childhood through to her time at the White House in this massive best-seller. ($28.59 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Beautiful Ones," by Prince: Readers see the artist in his day to day more than the larger-than-life figure shrouded in mystery in this memoir started before the author's death and finished by his collaborator, Dan Piepenbring. ($26.40 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Beautiful on the Outside," by Adam Rippon: The bronze medal-winning Olympian went to his Twitter feed for the title of his memoir: "With everything going on in the media about me this Valentine's Day I don't want people to get distracted and forget how beautiful I am (on the outside)." ($28 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Over the Top," by Jonathan Van Ness: The "Queer Eye" star's memoir is full of anecdotes, detailing everything from romantic relationship struggles to the death of his stepfather to skating on ice with Olympian Michelle Kwan. ($24.63 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Dear Girls" by Ali Wong: The comedian and actress's first book is everything her fans would expect: raunchy, real and uproariously funny. ($23.75 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Book club favorites"The Wives," by Tarryn Fisher: Thursday tries hard to be the perfect wife for Seth – even though he has two other wives who live in another city. Fans of "Gone Girl" will love it. ($12.40 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Evvie Drake Starts Over," by Linda Holmes: An extraordinarily ordinary adult love story about a widow falling for a baseball player past his prime. ($22.87 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine," by Gayle Honeyman: Eleanor Oliphant's isolated lifestyle changes when she befriends Raymond, an IT guy from the office, and Sammy, an elderly gentleman who has fallen on the sidewalk. ($13.71 paperback or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Writers & Lovers," by Lily King: In this late-blooming coming-of-age story, 31-year-old Casey Peabody struggles to reconcile who she wanted to be with who she's become after the death of her mother, a love affair gone wrong and with her novel still unfinished. ($21.06 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "The Giver of Stars," by Jojo Moyes: An unlikely group of women defy society's norms to deliver library books during the Great Depression. It's a stellar celebration of the power of reading. ($20.44 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Little Fires Everywhere," by Celeste Ng: Mia Warren rents a house in suburban Cleveland and causes upheaval in the neighborhood. Read along as you watch the ferocious new Hulu series. ($14.62 hardcover or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Where the Crawdads Sing," by Delia Owens: Reclusive Kya Clark is suspected in the death of handsome Chase Andrews. ($18.98 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Dutch House," by Ann Patchett: A doomed house, distant father and wicked stepmother forge an unbreakable bond between two siblings, who have only each other when all else is lost.($20.43 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Such a Fun Age," by Kiley Reid: When Emira, a black babysitter, is accused of kidnapping her young charge, a white child, her life and that of her employer, Alix, is turned upside down. ($20.54 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Nothing to See Here," by Kevin Wilson: An old high school friend comes back into Lillian's life, asking whether she can help her care for her two new stepkids. There's just one catch: The children catch fire. Literally. As in, they spontaneously combust. ($23.74 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Critically acclaimed modern fiction"All This Could Be Yours," by Jami Attenberg: One particularly damaged family experiences a reckoning when its toxic patriarch dies. Dark, witty and psychologically sharp. ($26 hardcover or $18.34 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Fleishman Is in Trouble," by Taffy Brodesser-Akner: "'Fleishman' is a highly entertaining novel about 40-something foibles, but it also delivers a piercing message about just how much within a relationship is prone to misinterpretation," says a ★★★½ review for USA TODAY. ($23.75 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Trust Exercise," by Susan Choi: "In her masterful, twisty fifth novel … Choi upgrades the familiar coming-of-age story with remarkable command and sensitivity," says a ★★★½ review for USA TODAY. ($23.75 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "City of Girls," by Elizabeth Gilbert: The author of "Eat, Pray, Love" sets this luscious love story in the New York City theater world of the 1940s, exploring female sexuality, promiscuity and fulfillment.($24.64 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Mirror & the Light," by Hilary Mantel: The final book in Mantel's stellar Thomas Cromwell trilogy finishes things off brilliantly. "Every page is rich with insight," says a ★★★★ review for USA TODAY. ($24.49 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "There There," by Tommy Orange: A moving and masterfully executed novel about the interconnected lives of Native Americans living in Oakland, California. ($25.95 hardcover or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Disappearing Earth," by Julia Phillips: Two sisters, ages 8 and 11, make the dreaded mistake of accepting a ride from a stranger, and a beautiful August day at the beach turns into every mother's worst nightmare in the far-flung reaches of rural Russia. ($23.71 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Normal People," by Sally Rooney: Two young people from different social and economic castes have an intense sexual affair, and an equally intense falling out in this novel that smartly explores dynamics between power, class and sex. ($22.87 hardcover or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Lincoln in the Bardo," by George Saunders: This exhilarating, theatrical novel about a grieving Abraham Lincoln visiting his young son's grave, narrated by a chorus of ghosts, is equal parts heartbreaking and hopeful, and one of the best books of the century so far. ($18.48 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Nickel Boys," by Colson Whitehead: The latest novel by the Pulitzer Prize- and National Book Award-winning author of "The Underground Railroad" is a powerful tale of two boys at a reform school in Jim Crow-era Florida. An instant classic. ($21.95 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Riveting nonfiction"The Body," by Bill Bryson: "Like a douser hunting water, Bryson is adept at finding the bizarre and the arcane in his subject matter," our critic said in a ★★★½ review. In this case, that subject is the human body. ($28.15 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "In Cold Blood," by Truman Capote: Considered by many to be the first true-crime classic, Capote details the murder of four members of the Clutter family in Kansas and the killers behind it.($14.07 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Guns, Germs, and Steel," by Jared Diamond: This 1998 Pulitzer-winning book reveals the geographical and environmental factors that shaped the modern world and allowed some cultures to become dominant over others. ($26.35 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Catch and Kill," by Ronan Farrow: The Pulitzer-winning investigative reporter shares his riveting account of investigating and reporting on Harvey Weinstein. It's nonfiction that reads like a thriller. ($24 hardcover or $15.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Office: The Untold Story of the Greatest Sitcom of the 2000s: An Oral History," by Andy Greene: This oral history of the cult-favorite sitcom that exploded into a major phenomenon on Netflix years after it ended features interviews with nearly 90 cast and crew members plus executives and critics. ($20.44 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Sapiens," by Yuval Noah Harari: The historian explores the ways in which biology and history have defined humanity and examines the role evolving humans have played in the global ecosystem. ($18.24 paperback at Books-A-Million) "The Devil in the White City," by Erik Larson: The story of an architect, Daniel H. Burnham, and a serial killer, Dr. H.H. Holmes, is juxtaposed against the 1893 Chicago World's Fair. ($11.56 paperback or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Destiny of the Republic," by Candice Millard: The life of James A. Garfield is traced from his impoverished birth to becoming president of the United States – and in particular, his being shot by a deranged office-seeker and the political and medical drama that ensued before his death. ($14.95 paperback or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Library Book," by Susan Orlean: This book details the story of the devastating 1986 fire at the Los Angeles Public Library, which destroyed or damaged more than a million books. ($24.64 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Secret Lives of Color," by Kassia St. Clair: This collection of riveting micro-histories on colors includes where they come from, how they fell in and out of vogue and the roles they've played in society. ($20 hardcover at Books-A-Million) Classics"The Handmaid's Tale," by Margaret Atwood: Revisit the feminist dystopian masterpiece resurrected by the Hulu series. The long-awaited sequel "The Testaments" is also well worth a read. ($10.05 paperback or $3.39 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Emma," by Jane Austen: Read this delightful comedy of manners about romantic misunderstandings, then catch the new film adaptation starring Anya Taylor-Joy as the would-be matchmaker. ($5.95 paperback or $8.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "If Beale Street Could Talk," by James Baldwin: A young black couple is tested when Fonny is falsely accused of rape and Tish finds out she's pregnant. Read the tragically beautiful book, then watch the equally tragically beautiful film adaptation. ($14.95 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Jane Eyre," by Charlotte Brontë: An orphaned young governess, a love affair with brooding Mr. Rochester, a secret crazed wife locked in the attic – what's not to love? ($5.95 paperback or $4.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Middlemarch," by George Eliot: This is one of those big books you always meant to read that you definitely should (it's probably been sitting on your shelf for decades). Read along with book podcast Literary Disco. ($7.95 paperback or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Great Gatsby," by F. Scott Fitzgerald: Revisit the Roaring '20s, where the American dream goes to die over champagne cocktails. It's just as decadent and relevant nearly a century after publication. ($13.71 paperback or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "To Kill a Mockingbird," by Harper Lee: We know, we know – nothing could be more obvious. But some things are obvious for a reason: This coming-of-age story set in the Jim Crow South was named "America's best-loved novel" by the PBS series "The Great American Read." ($15.83 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Razor's Edge," by W. Somerset Maugham: An American pilot traumatized by World War I sets off in search of transcendence. ($16.95 paperback or $13.99 at Books-A-Million) "The Bluest Eye," by Toni Morrison: We lost one of the greatest writers who ever lived when we lost Morrison last year. Start with her first book, about a young black girl who longs to look like Shirley Temple. ($13.15 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "War and Peace," by Leo Tolstoy: Clocking in at over 1,000 pages, this Russian classic is many readers' white whale. Literary magazine A Public Space is making it feel conquerable with a guided reading by writer Yiyun Li. ($24.99 paperback or $1.77 ebook at Books-A-Million) Modern romance and romantic comedies"Bet Me," by Jennifer Crusie: After going to dinner with a man who asked her out only to win a bet, Min Dobbs cuts her losses, but fate has something else in mind. ($25.99 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Bridget Jones's Diary," by Helen Fielding: Thirty-something singleton Bridget Jones chronicles her yearlong quest for self-improvement, which includes reducing the size of her thighs and forming a functional relationship. ($16 paperback or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Proposal," by Jasmine Guillory: When a public marriage proposal at a Dodgers game does not go as planned, Nikole Paterson's life takes an interesting turn. ($13.20 paperback or $2.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Confessions of a Shopaholic," by Sophie Kinsella: Financial writer Becky Bloomwood has a fabulous life filled with all of life's must-haves. The only problem? She is in massive credit card debt. ($14.07 paperback or $4.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Red, White & Royal Blue," by Casey McQuiston: Alex Claremont-Diaz is the handsome, single son of the American president, and he's got a beef with Prince Henry across the pond that turns into something more. ($12.40 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Me Before You," by Jojo Moyes: This unlikely love story is set in a small English village, in which a young woman helps care for a 35-year-old quadriplegic. ($14.07 paperback and $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Flatshare," by Beth O'Leary: This charming book is a traditional romance revival with a delightful twist: Two roommates on different work shifts share a bed and fall in love by communicating through sticky notes. ($26.99 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "The Rosie Project," by Graeme Simsion: Don Tillman, a socially awkward man, decides it is time to wed and embarks on The Wife Project. Along the way, he meets a young woman searching for her biological father. ($14.94 paperback or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Hating Game," by Sally Thorne: Lucy Hutton and Joshua Templeman's relationship goes from bad to worse when the executive assistants to co-CEOs are both up for the same promotion. ($13.19 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Bookish Life of Nina Hill," by Abbi Waxman: Nina Hill is content in life until she discovers a father she never knew existed and an inheritance she never wanted. ($14.07 paperback or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Sci-fi and fantasy"Children of Blood and Bone," by Tomi Adeyemi: This West African-inspired fantasy is set in the newly magical world of Orïsha, and is followed by the excellent sequel, "Children of Virtue and Vengeance." ($13.86 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Parable of the Sower," by Octavia E. Butler: It's 2024, society is collapsing due to the catastrophic effects of climate change, and teen narrator Lauren Oya Olamina begins to develop her own religion, called "Earthseed." There's even a graphic-novel adaptation. ($14.94 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Stories of Your Life and Others," by Ted Chiang: Chiang is one of America's preeminent science fiction writers. This collection of short fiction features "Story of Your Life," the Nebula Award-winning novella that inspired the 2016 film "Arrival" (also brilliant). ($14.91 paperback or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?" by Philip K. Dick: Most moviegoers know this novel better as the inspiration for the 1982 film "Blade Runner." In it, Bounty hunter Rick Deckard tracks down androids living among humans in a post-apocalyptic San Francisco. ($14.07 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "American Gods," by Neil Gaiman: Shadow, an ex-con whose wife and best friend are killed in a car crash, takes a job as a bodyguard for a mysterious figure and finds himself in a world where old gods battle the new gods of consumerism and technology. ($27.99 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Dune," by Frank Herbert: This sci-fi classic tells the story of a boy named Paul Atreides who goes undercover to seek revenge for his noble family, the victims of a traitorous plot. The novel was the first-ever winner of the Nebula Award and is being adapted into a new film this year. ($9.66 paperback or $1.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Vanished Birds," by Simon Jimenez: Nia Imani travels through space in a ship that speeds faster than light, a woman out of time. Until, while visiting one planet, a mysterious boy falls from the sky. ($23.75 hardcover or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Zed," by Joanna Kavenna: This clever, satirical, dystopian novel imagines an orderly technotopia run by a megacorporation thrown into chaos by glitching tech. A world made perfect by an algorithm isn't so perfect after all. ($27.95 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "A Game of Thrones," by George R.R. Martin: You've seen the series, now read what it is based on. The first novel in "A Song Ice and Fire" series opens with trouble and winter descending on Westeros. ($30.88 hardcover or $8.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Martian," by Andy Weir: An astronaut is stranded on Mars and must find his way home after he is unintentionally left behind. The novel was made into a 2015 film starring Matt Damon. ($14.95 paperback or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Mysteries and thrillers"And Then There Were None," by Agatha Christie: The whodunnit that is considered a classic example of the locked-room mystery follows strangers stranded on a remote island who discover there is a murderer among them. ($7.99 paperback or $3.39 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Gone Girl," by Gillian Flynn: When Nick Dunne's wife Amy disappears on their fifth anniversary, he's suspect No. 1. But this book is a lot more demented than a simple whodunnit. A lot more. ($23.75 hardcover or $8.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Maltese Falcon," by Dashiell Hammett: Private detective Sam Spade is hired by a mysterious woman to follow the man her sister has run away with and becomes entwined in the search for an elusive statuette. This is the real deal: Hammett's prose goes down like a shot of whiskey. ($15 paperback or $10.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Woman in the Window," by A.J. Finn: Anna Fox, a 38-year-old woman in New York City who self-medicates and spies on her neighbors, is convinced that she has witnessed a crime committed in the townhouse across the park. ($12.34 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Someone We Know," by Shari Lapena: A teenage boy breaks into neighborhood houses and steals secrets off the families' computers. "As the story quickly progresses, so do the clever plot twists and turns," USA TODAY says in a ★★★½ review. ($23.75 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Spy Who Came in From the Cold," by John le Carré: Facing retirement as head of the Berlin Station, Alec Leamas is given an opportunity to avenge his fallen comrades. ($28 hardcover or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Chain," by Adrian McKinty: When Rachel's 13-year-old daughter is kidnapped, she receives a phone call letting her know she is now part of the Chain – and that she must kidnap another family's child for her own to be released. If the chain is broken, her daughter will die. ($28 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Big Little Lies," by Liane Moriarty: The lives of three mothers are linked together by their kindergartners – and possibly a murder. In a ★★★ review, USA TODAY called it "a fun, engaging and sometimes disturbing read." ($23.71 hardcover or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Devil in a Blue Dress," by Walter Mosley: Ezekiel "Easy" Rawlins, a black war veteran, just fired from his job at a defense plant, is approached by a stranger who offers him a job finding a young white woman in 1948 Los Angeles. ($16.99 paperback or $12.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Woman in Cabin 10," by Ruth Ware: Travel writer Lo Blacklock sees a woman thrown overboard on a luxury cruise, but unfortunately no one believes her. ($14.07 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Cookbooks"The Bread Bible," by Rose Levy Beranbaum: The cookbook contains 150 recipes, including yeasted bread, quick bread, flatbread and pizza dough. ($30.88 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Mary Berry's Baking Bible," by Mary Berry: Fans of "The Great British Baking Show" have already streamed the series multiple times. With this book, they can try their own hand at the judge's signature bakes, including Victoria Sponge, Mokatines and Madeira cake. ($43.95 hardcover or $26.37 ebook at Books-A-Million) "How to Cook Everything: The Basics," by Mark Bittman: The veteran cookbook author tackles the basics of cooking every home chef should know, from dicing to roasting and everything in between. ($32.55 hardcover or $26.05 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Mastering the Art of French Cooking," by Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, Simone Beck: The cookbook is a classic that inspired Child's TV show, "The French Chef," and later a blog, the Julie/Julia Project, followed by the feature film "Julie & Julia."($35.20 hardcover or $22.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Pioneer Woman Cooks," by Ree Drummond: The origin of the Pioneer Woman was a blog that then begat cookbooks and a television show. This was the first of her cookbooks to be published and was an immediate success.($20.57 hardcover or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Magnolia Table," by Joana Gaines, Marah Stets: The co-star of HGTV's departed design and renovation show "Fixer Upper" and co-founder of the Magnolia empire shares her favorite recipes for gatherings. ($26.39 hardcover or $19.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Carla Hall's Soul Food," by Carla Hall with Genevieve Ko: The "Top Chef" alum shares her favorite recipes and traces the history of comfort cuisine from Africa to the Caribbean to the American South. ($29.99 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat," by Samin Nosrat: The author espouses a new cooking philosophy – simply master those four elements and anything you cook will be delicious. ($33 hardcover or $19.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Antoni in the Kitchen," by Antoni Porowski, Mindy Fox: The "Queer Eye" star shares favorite recipes and personal anecdotes in this "culinary memoir." ($26.40 hardcover or $21.15 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Martha Stewart Cookbook," by Martha Stewart: Sure to keep you busy, this classic 1995 cookbook has more than 1,400 recipes that are compiled from Stewart's original books. ($2.99 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "Cravings," by Chrissy Teigen with Adeena Sussman: The model-turned-lifestyle celebrity's first cookbook was also the first to debut at No. 1 on the USA TODAY Best-Selling Books list. We took some of the recipes for a test drive and they passed. ($29.99 hardcover or $7.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) Sports"Friday Night Lights," by H.G. Bissinger: An in-depth look at a single season of a high school football team, the Permian Panthers, of Odessa, Texas, where football is king. ($29.99 hardcover or $9.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Boys in the Boat," by Daniel James Brown: The extraordinary journey of the eight-oared crew from the University of Washington and their quest for gold at the 1936 Berlin Olympic. In a ★★★½ review, USA TODAY called it "a surprisingly suspenseful tale of triumph." ($17 paperback or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Boys of Winter," by Wayne Coffey: The story of the gold medal-winning U.S. Olympic hockey team, which defeated the Russians at the height of the Cold War in 1980. ($15.12 paperback or $11.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Ali: A Life," by Jonathan Eig: Biography of the boxer who floated like a butterfly and stung like a bee and would go on to become "The Greatest." ($17.99 paperback or $12.74 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Seabiscuit," by Laura Hillenbrand: A small, crooked-legged racehorse rises from obscurity to become a champion thoroughbred and sports icon in Depression-era America. ($18 paperback or $13.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "The Boys of Summer," by Roger Kahn: A sentimental account of the Brooklyn Dodgers, from the author's childhood memories, traces their path to victory in the 1955 World Series to later years of the team's beloved players. ($15.83 paperback or $14.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Moneyball," by Michael Lewis: The book focuses on the 2002 Oakland Athletics and the team's efforts in using a new statistical model to field a successful team. ($26.95 hardcover at Books-A-Million) "All the Way: My Life in Four Quarters," by Joe Namath: The celebrated New York Jets quarterback led a remarkable life. He not only beat the Colts, he whooped alcoholism and evolved into a doting grandfather. ($26.40 hardcover or $15.99 ebook at Books-A-Million) "Only the Ball Was White," by Robert W. Peterson: A look at the forgotten story of baseball's Negro Leagues from post-Civil War to 1947, when Jackie Robinson was signed to the Dodgers. ($19.99 paperback at Books-A-Million) "Paper Lion," by George Plimpton: In this classic of sports journalism, the author recounts his experiences in training camp and in practice with the 1963 Detroit Lions. ($20 paperback at Books-A-Million) The product experts at Reviewed have all your shopping needs covered. Follow Reviewed on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram for the latest deals, product reviews, and more. Prices were accurate at the time this article was published but may change over time. Read or Share this story: https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/reviewedcom/2020/03/28/coronavirus-100-books-read-while-stuck-home-social-distancing/2909337001/ |

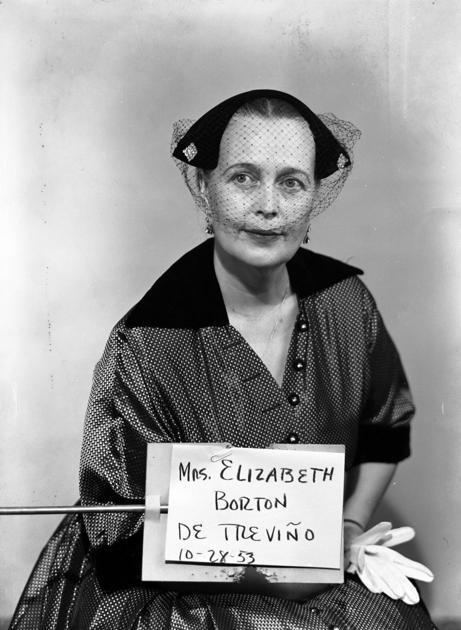

| Posted: 28 Mar 2020 12:00 AM PDT  "Beth Treviño's Books Are Aid to International Understanding," proclaimed the headline of an article in the May 21, 1966, Bakersfield Californian. Spanning 50 years, several books and publications, Elizabeth Borton de Treviño dedicated her writing career to telling stories that crossed borders and cultures. Mary Elizabeth Victoria Borton was born in Bakersfield in 1904 to local attorney Fred Ellsworth Borton and Carrie Louise Christensen. The love of writing was instilled in her at a young age by her father who also wrote poems and short stories. After graduating from Kern County High School in 1921, Borton de Treviño attended Bakersfield College for two years before she was accepted into Stanford University. While there she became a member of Phi Beta Kappa and was one of 30 students to graduate in 1925 with the Distinction of Great Honor. The next phase in her life took her to Boston, where she was on the staff of the Boston Herald. She spent some time in Hollywood interviewing movie stars, but it was while on assignment in Monterey, Mexico, that her life changed. Upon her arrival, she was introduced to Luis Treviño Gomez. He was assigned as her interpreter and it did not take long before the two fell in love. After wedding in 1935, the young couple moved in with Luis' parents before setting off on their own and having two sons, Luis and Enrique. Soon, Elizabeth embarked on a journey of creating literature that appealed to book lovers around the world. Her passion for her adopted homeland was interwoven thoughout the stories she told of old Mexico and Spain and in a series of memoirs. In 1966, she was awarded the Newbery Medal for the most distinguished contribution to the literature of children in English for "I, Juan de Pareja," which recounted the story of famous artist Diego Velazquez and his African slave Juan, who went on to become an accomplished artist in his own right. Even with her success, Bakersfield was never far from her mind and she frequently returned to visit with family and to share a picture of her life in Mexico with various community groups. It was during these talks she recounted stories about the customs, education and culture of our southern neighbor. Borton de Treviño's nonfiction work really embodied the spirit of multiculturalism and love. Her memoir, "My Heart Lies South: The Story of My Mexican Wedding," tells the story of family, love and the blending of cultures. Excerpts from the book were prominently featured in national magazines, condensed by Reader's Digest, and translated into 14 languages and Braille. On Nov. 15, 1962, The Californian praised Borton de Treviño's follow-up memoir, "Where the Heart Is," for its international understanding and deep appreciation of another country's culture. Borton de Treviño provided a "fresh, humorous and deft" account of life with her Mexican in-laws, her children with their Gringo-Mexican heritage, her husband, friends, neighbors and pets. Reminding others about the importance of acceptance and love, Borton de Treviño wrote in a 1971 epilogue to "My Heart Lies South": "You must love each other. If you marry across racial, religious and cultural lines, you must love more and harder."  |