“Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine

“Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine |

| “Paciente Cero,” a new short story by renowned Mexican author Juan Villoro. - Slate Magazine Posted: 28 Mar 2020 12:00 AM PDT Janina Romero Each month, Future Tense Fiction—a series of short stories from Future Tense and Arizona State University's Center for Science and the Imagination about how technology and science will change our lives—publishes a story on a theme. The theme for January–March 2020: politics. Translated by Will Vanderhyden.

1. What's Left of the WorldI was born in a distant time, when vanilla ice cream was yellow. The world had agreed it should be that color, but later in the 21st century it was changed to red. They say more is consumed now. People want red things. Dr. Fong is an herbalism aficionado. He concocts a vanilla extract the color of coffee. I asked if he'd ever considered dying it red. "Reality fakes colors, no need for us to," he said. I go visit him every three days to play chess. There's little to do under the violet clouds of Ciudad Zapata. The air here has a particular density; every morning I clean a film of dust off my desk. Those particles come from infinite waste. I thought it'd give me vertigo to imagine all the things and all the people who become the powder I wipe off my desk (what's left of the world), but the real surprise was that I feel nothing. At 91 years, habit is my medicine. Fong has asked me to write. To tell a story, knowing stories are no longer told. I've lived long enough to bear witness to the loss of my occupation, not an uncommon experience in the end. (My father worked at a printing press and my grandfather was a telegraph operator.) In 2020, three decades ago, I took a taxi. The driver asked me what I did for a living and didn't understand my answer. "Literature?!" he exclaimed. At the time, it struck me as ignorant; now I know it was prophetic. Old people are athletes; every movement is an extreme sport for us. If I spend half an hour in a chair, I know what'll happen to me when I stand up: pain in every joint. I have to go to the bathroom all the time. I'm so conditioned by the pain that just the idea of walking makes my knees hurt. People who play sports through injuries know the feeling: They're old in anticipation. Transitioning from stillness to movement is hard for me, but I can still walk the kilometer that separates my bungalow from the Processing Office. The route is safe. They no longer publish crime statistics. We intuit them based on increases or decreases in private militias. The guards greet me on my way to Fong's studio, raising a fist, encouraging an old man's marathon. Some belonged to previous outfits and use a mix of uniforms, like soccer players swapping jerseys. At the entrance to the Office, there's a metal detector, not particularly effective in the era of refined polymers. I set it off with my artificial hips and maybe even with my teeth; they contain more metals than the guards' service weapons. I leave home at 4, prime time for the heat of the machines to swathe me like cotton, relieving the cold in my hands. I make sure to return home before the neon ideograms light up and the scattered lamentations of mariachis animating the Chinese cantinas fill the air. Migrants are coming to Ciudad Zapata in search of work. By day, they grow like shadowy and wandering silhouettes. By night, they sleep on the esplanade under the open sky. On my way home, I see that horizontal nightmare: bodies stretched out like the corpses from a cataclysm. Not even the rain drives them away. They wait, and sometimes die out there, as if persistence would grant them rights. On the hottest days, when the wind blows toward my bungalow, an unmistakable aroma reaches me, the bitter odor of poverty. This is uncomfortable, but doesn't alter my habits (my medicine). Fong doesn't complain about this country either. He was dispatched here to take charge of the vast waste zone, after previously working in Southeast Asia and South America, heading up projects another kind of person would've been more boastful about. Despite his discretion, I know he graduated with honors in the field of zoonosis. The genetic modification of mosquitos eradicated malaria and other diseases, but increased the populations of animals that infect people. Fong was responsible for the cordons sanitaires that protected them from new swine and monkey viruses. He calls that time, which others might describe as heroic, "the time of the hecatomb," specifying that "hecatomb" refers to the ritual sacrifice of 100 oxen. While attacking my king in a game of chess, he talks about the millions of animals sacrificed so people could live. "Destroying trash is more relaxing work," he says, smiling. He talks about his country with statistical reverence and offers data on famines, deaths, and epidemics. He doesn't suffer nostalgia: He never goes to Swallow's Nest, Lucky Star, or the other restaurants that cater to the Chinese community. His cozy studio is furnished with Western antiquities: two rocking chairs, a coat rack, a piece of furniture with small drawers that once served as a reliquary in a church, threadbare rugs of complex fabrics. The room is presided over by a copy of Hieronymus Bosch's The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. I admire that elaborate fantasy, but prefer to sit with my back to it. The window looks out on a greenhouse where Fong grows orchids. The greenhouse's glass panes, of an extreme thickness, protect from the flashes and temperature fluctuations on the outside, where trash is slowly being transformed into energy. Rumors are necessary for maintaining order. Once, I went into Fong's work area, quite different from his private quarters. His assistant (whose name I don't know, but whom I call Chucho without any protest from him) is proud of his "programmable matter" device. He needs only to press a button to transform a cellphone into a laptop. Dr. Fong took the time to explain to me that this transfiguration is possible because the device's network of catoms (claytronic + atom) alters its programming and takes on other functions. The metamorphosis seemed both brilliant and unnecessary, conceived of for Chucho's entertainment (like turning a frog into a rabbit). Moore's Law, formulated way back in 1965, predicted the power of computers would double every two years, and then came the quantum expansion. Technology has created increasingly inscrutable gadgets, but Chucho will always be Chucho: If he presses a button, he expects a surprise. After showing me the "programmable matter," Fong asked, "What're you doing Sunday?" "Nothing," I said, which wasn't true. (I was supposed to go with Ling to the boring warehouse where she returns the goods that she purchases remotely but turn out to be different from the holograms promoting them.) The odd thing about the conversation was that Fong thought Sunday existed. It's hard to believe he ever takes a day off. I've heard rumors about the corruption of the Chinese managers. Back when I was still interested in ideology, I understood that their global supremacy depended on combining the defects of communism with the defects of capitalism. Later, I came to accept it as a natural product of the food chain. Someone has to take the last bite and I'd rather it be the Chinese, who in a way have saved us. Rumors are necessary for maintaining order, which Fong loves so much. The illusion of crime—the idea somebody might still commit one—is reassuring, because it's nothing but fantasy. Discussing corruption satisfies the residual longing for disorder that still lives on in thinking predators. Crime has become an unrealizable possibility and only takes place on a conjectural plane. I know this now, but shouldn't get ahead of myself in the story.

2. Lead, Carbon, SiliconeThat Sunday, I went outside the city with Fong. He came to pick me up in one of those customized trucks, outfitted with lead armor plating, which became popular when attacks were frequent and the Law of Transportation reduced the speed limit to 30 kilometers per hour. Fong pointed at the hood: "The lead protected against bullets and now protects against radiation. It's one of my favorite elements." This raised a question I couldn't ask anybody else: "What element do you mistrust?" "Silicone, of course! It's too common, the second most abundant element after oxygen. Transistors and transformers exist because of silicone. It's the new clay, 'programmable matter.' If a religion were invented today, God would mold people out of silicone." From there, we moved on to the I Ching. The doctor spoke of oracular mutations until he remembered the subject had arisen from silicone: "Imaginary transformations are good and real ones are acceptable. Transformations that are too real are the real problem." "How can something be too real?" "When it can no longer be imagined." "I don't understand." "You will." "At 91 years old, my expectations of learning anything are low." "Don't throw in the towel, professor," he smiled. We continued slowly on our way. In my old age, I've achieved leisure without being freed from anxiety. I hate the slow machinery of the new vehicles. Fong, on the other hand, adapts to every circumstance. I don't know if it's because he suppresses his reactions with furious discipline or if he's in possession of a fluid temperament that prevents distress. The truth is, I've never heard him complain. Because of the rains and the total lack of maintenance, the highway has holes the size of craters; in one, some vultures picked at an animal carcass. We slowed down and a group of half-naked children surrounded us to ask for spare change. Their teeth were brown from the chemical waste that leached into the water tables. Fong lowered the window and tossed them a bag of Chinese candy, with a calm expression, like a godfather throwing coins after a baptism. I was flattered Dr. Fong sought out my company. The man who runs the world's largest waste emporium is interested in me. Old age destroys one's prostate or ovaries, never one's vanity. We passed scraggly garden plots and little stores that popped up between trash dumps, until we came to something resembling a town: small colored houses, a wire arch that in another time held up brightly colored streamers of papel picado, a hammock store, a stand selling plants, maybe fruit trees. The asphalt blended with the gravel until we came to a basketball court. The backboards advertised a vanished soft drink brand and the baskets had no nets. In the middle of the court was a table. Four of the half-dozen chairs were occupied. We left the car in the shade of a laurel with leaves the color of mustard and walked to the two chairs reserved for us. "Welcome to the playground of the world!" the oldest one—quite a bit younger than me—said. "It's a pleasure to see a man of sound mind." That was the courteous way he referred to my age. "The years pass, but the game never changes: One hoop leads to day, the other leads to night; one to woman, the other to man, the eternal dualities. You wrote an article about that." "Centuries ago," I smiled. "You didn't bring a hat?" a woman asked me. We were out in full sun. Fong was wearing a palm hat. A man handed me a cap promoting a vanished political party. "I'd rather get sunstroke," I said, with a touch of my useless childish indignation. "The heat is the fault of the Chinese," another woman joked. This was true: The processing plants have increased the ambient temperature by 5 degrees (a wonderful thing, when you're 91 years old). They gave me a hat somebody else had already been wearing. I felt the sweat of another touching my forehead, but didn't take it off. Fong explained that these people were delegates of the Indigenous Council with whom he addressed "problems in the sector." From beginning to end, the delegates (two women and two men) carried the conversation. At one point, Fong wanted to change the subject and they asked him to respect the Agenda. He acquiesced, motivated by a deep respect or his military training. I didn't know what kind of representation our interlocutors had. I assumed the "council" to which they belonged was nothing more than an imaginary group or a guild. It bothered me when they compared the Founding Hero to a landowner who treated the country as if it were his own estate, but above all I was alarmed they thought I agreed with them. (One even suggested we'd met before.) I wanted to leave, but Fong took me by the arm. The Founding Hero has been governing so long it's no longer worth tracking the time ("I'll remain as long as the people ask," is his slogan). At his long rallies, he doesn't fall into the banality of referring to his enemies as evil. He calls them "reckless," "irrelevant," "lunatics," "egomaniacs," "chancers." This last insult is my favorite; it refers to those ne'er-do-wells who live off the opportunities offered by the State. I've resigned myself to being a chancer. On the basketball court, presented as the "playground of the world," I felt I was in the company of the Founding Hero's true adversaries. The fear of being caught with them only increased when they attempted to calm me: "We're in a valley and the stone contains a lot of minerals: Carbon doesn't transmit here." My anxiety didn't fail to comply with the norms of biosecurity, because I couldn't be detected. That worried me more. I was forming part of an operation. Why had Fong led me into that ambush? One of the women took out an old newspaper clipping. Despite the fading print, I saw my own face. "You used to be with us," she said. The Founding Hero has been governing so long it's no longer worth tracking the time. I couldn't make out the scene (a public plaza in an unrecognizable city), but a sensory confusion overcame me. Thirty years ago, I participated in activities I've managed to forget. In that naïve time, ethnicity was all the rage. The most diverse objects were decorated with indigenous motifs. Slippers, folders, plastic boxes, cellphone protectors, pajamas, jackets, paper napkins, tablecloths, swimming suits, and towels alluded to Antillean, Inuit, African, or Mesoamerican (taken together, they seemed to emulate peoples of Oceania) ethnicities. Lip service was profusely paid to the original peoples, pushed off their tribal lands. It only served to increase the varieties of indigenous-inspired wallpaper and allowed the Founding Hero to promote his Progressive Development Plan. What'd I been doing at that time? I didn't want to remember. Fong intervened. He said that the Chinese and Mesoamerican civilizations had known such splendor that could only now be recovered through legend; in Beijing or Mexico City the present would never be as strong as the past. As an expert in zoonosis, he remembered that our countries broke news with infections (the swine flu of 2009 and the coronavirus of 2020). "They take us into account when we get infected," Fong said. "The people most resistant to threats are the ones who have suffered the most because of them," referring to our host, presumably, but also to the thousands of Chinese who had lived invisibly in Mexico, on the margins of documentation and statistics. When it was created, the Ministry of Biosecurity had no reliable data on the Chinese or the indigenous peoples. Even today, they remain a dark zone, of little interest to the Founding Hero, because of their minority status (he limits himself to reiterating the number of his millions of supporters). I noticed that Fong was only speaking to me. The rest of them were already aware of what he was saying and listened impassively, which alarmed me: "The alliance among undocumented people must have taken place long ago, but the Chinese immigrants were devoted to their small shops, using passports of dead people, and the indigenous people were displaced from their lands. When I arrived here, several years ago now, I suspected there were immigrants among the plant employees. They were whimsical and distracted, but they pretended to be disciplined. The enigma of their behavior intrigued me and I didn't report them. When I met the people from the Indigenous Council, I knew they'd also escaped the Ministry of Biosecurity's carbon chips." He adopted the detached tone he used when getting sidetracked during our tea and chess sessions: "After combating epidemics, I became interested in a possibility: choosing my own disease." As he spoke, he softly tapped the table, as if it were a keyboard. One of the women imitated him. It was as if they were communicating in Morse code. Fong smiled seeing how her gesture coincided with his own: "I don't belong among the old immigrants: I'm Chinese from China," he brought two fingers to his head, a signal that he had carbon conductors implanted there, "but we didn't come here to talk about this." They handed me a document that explained my presence there. They wanted me to review the wording. I read an archaic message about the rights of the original peoples riddled with the word hope. The wording seemed correct to me; I only had to cut words that had fallen into disuse and adjust the punctuation, which I found rushed. "We learn from our mistakes." With those words from the doctor, my corrections were approved. The others thanked me and gave me a weaving, with the image of a smiling sun embroidered on it. The air smelled of roasted corn. The meeting wrapped up quickly and I feared they wouldn't give us anything to eat. But they gave us some tamales for the road. Fong was kind enough to give me his. I ate the luscious masa as if returning to my childhood. I found the concept of "a man of sound mind" flattering, but applied to me it could only be ironic. One scene summed up our trip: When I handed back the corrected document, Fong gave me the same soft smile I'd seen him give his "programmable matter." My encounter with the indigenous council had been a test.

3. Green TeaI came to Ciudad Zapata after my third retirement. Cuts in the cultural sector had forced me to accumulate three pensions. After decades of writing for a journal that achieved the artisanal glory of being printed, for a news agency, and for a state-run publishing house, I was able to retire. Obviously, it would've all been far simpler if I hadn't been married three times. With the current laws, even moving to Venus won't save you from paying alimony. But I can't complain: Ling accompanies me with the shifting constancy of the phases of the moon. Though she's here with me, she comes and goes. There's little physical contact between us, apart from when she puts the Stygian drops in my eyes, to lengthen my life or maybe preserve my eyesight. When she stands up from the table or says goodbye, she touches me with distracted tenderness. That's not what keeps me by her side. Our lives crossed like two contrails in the sky. I've been captivated by this phenomenon multiple times: One white slipstream begins to dissolve overhead as another passes through it, giving it new meaning. Why did Ling decide to stay with me (it would be sad to say "accept")? She's among the 90 percent of women who aren't granted fertility authorization. Having a young partner wouldn't provide her the benefits of procreation. Relationships have been devalued. Tellingly, they are considering building the primary penal colony on Venus, the ancient planet of love. Ling likes young men with beards. She goes out with them until the night they start crying hysterically. "Pretty boys are weak," she says, with the serenity of someone speaking to a man too old to care about being ugly. For me, libido is a pleasant variation on the theory. I imagine Ling's erotic encounters without losing any affection for her. We coexist in a harmony only people who expect little from each other can attain. Ling arrived with the founders of Ciudad Zapata. She and I met in the capital, at my last job, which no longer paid out any pension. In 2030, at 73 years old, I was a teacher of Linguistic Normalization. My students had come to Mexico along with the global trash crisis. For decades, China bought trash from the United States and processed it within its own borders. Social demands and sanitary emergencies made it so impossible for China to continue absorbing such a vast quantity of waste. (Laid out flat, it would have covered the entire surface of Australia.) A new space was needed for all that trash, preferably somewhere near the United States. And so, to that end, the Founding Hero offered up the states of Michoacán, Guerrero, Jalisco, Nayarit, and Colima. The chancers said the Pacific coast would become a landfill for hire, but the Founding Hero had an additional agenda: finally cracking down on organized crime in the region. The drug cartels who controlled the area were pushed out by Chinese-backed occupation forces sent from the capital, to make way for a far greater business: the trash of the world. Ling took my Basic Spanish class. The Founding Hero claims everything can be said with the meager vocabulary he deploys at his rallies. Literary genres have disappeared or become hermetic. In a strict sense, this story is written in code. I miss literature, but I must admit that Ling's limited range of phrases eliminates emotional issues. Sometimes she has a random poetic impulse. She spoke to me of the shadows lengthening under the red sky of Ciudad Zapata, where trash burns 24 hours a day: "I would like to see your shadow there." Romantic advances in the workplace are frowned upon. I hadn't made the slightest attempt to approach Ling; six decades and thousands of words separated us. I admired her flowing hair and silky silhouette with the removed perspective of someone staring at a sunset. But Ling saw something in the few words I taught her. She spoke of my shadow and I quit my job to go with her. Her family had arrived in Mexico with the Tlaltecuhtli Project. The Founding Hero decided to honor the Aztec goddess who devours corpses while giving birth—the perfect symbol for recycling—but the name turned out to be unpronounceable for the Chinese. And so the main plant and accompanying buildings were christened Ciudad Zapata. I remember the photographs that spun around the mediasphere: the Founding Hero and the Chinese head of state breaking bread at a banquet where they served red—the new color of vanilla—ice cream. The lifeless streets of the city-plant bored me. The U.N., which is devoted to the harvesting of amusing data, claims Mexico is one the few countries where street dogs are still prevalent. None of them are in Ciudad Zapata. I appreciated the purr of the engines processing the waste, the red sunsets, the faint chemical odor that hangs in the air, but I understood why the Chinese took refuge in tequila and sad ranchera songs. Dr. Fong is Ling's great uncle. She took me to see him to give me something to do. She left us alone, as if we should have been celebrating an agreement. I thought the doctor would criticize me for sharing my life with a woman six decades my junior, and in a way he did. He quoted Confucius: "Before you embark on a journey of revenge, dig two graves." He had cause to object but no desire to resort to it. Our friendship sprang out of that avoided dispute. Fong is a biologist, specializing in zoonosis, but his training also includes crystallography, digital programming, linguistics, and ecology. In his country, he has a military rank. He operates with the methodology of someone who knows how many pills are left in his bottle of painkillers. (I put it to the test once when I had a headache and it didn't surprise me he knew the number.) Even in his hobbies, he acts like an expert: He lets me play with white, but always wins our games of chess. He masters Spanish with old-school rigor. I asked him what he thought about the Founding Hero calling the country the "nursery of recycling" and he said, "I've spent a great deal of time in the dangerous company of geologists: We've wiped out flora that's been around for 85 million years." It would've surprised me if he contradicted the Founding Hero. He didn't, but I was struck by the adjective dangerous being applied to geologists. The green tea Fong drank had a strange aftertaste. At first, I was afraid it was a diuretic and would force me to painfully get up to go to the bathroom. The odd thing was its smell and consistency, slightly mossy. For decades I drank coffee with the desperation of someone who needs energy to pay alimony. I know little about tea, but even I could tell there was something special in that substance. I didn't dare mention it during our first encounters. I put off my question until it became a secret. Once my visits had become routine, I got up the nerve to broach the subject. Fong answered: "The tea has rue leaves in it. Do you remember Pedro Páramo? The protagonist keeps a portrait of his mother in the company of some rue leaves. Rulfo knew what he was talking about: Rue combats the 'evil eye.' " I don't know if Fong really talked like that or if the tea helped me hear him that way. He continued his explanation: "This has a scientific basis: rue—Ruta graveolens, also known as 'herb-of-grace'—gives off a powerful electric charge and combats ills attributed to curses and extreme ennui. [He paused, took a long sip, and I thought maybe he was drinking another kind of tea.] It also affects carbon atoms," he added. There was nothing more to add. I was dumbfounded and he took advantage to take my picture. The lens looked to me like the eye of a cyclops or minotaur as Fong smiled: "I'll store your portrait with some rue leaves." "Where do you get the plants?" "From the people you met on the basketball court." He walked, with enviable agility for an 82-year-old man, to the wall that ran adjacent to the window. He pulled back a curtain, revealing a painting made of colored yarn. I could see asterisks, spirals, the antlers and eyes of deer. "Beautiful, right? Huichol art," Fong said. "The most interesting thing is that it worked for a healing. A patient was cured by looking at it." His voice quavered on those final words. I thought I understood that he was that patient. "What happens with the carbon?" I asked. "What happens with the carbon?" I asked. "There are things I should tell you and things you should think over on your own." Though his words had an oracular solemnity, I found them amusing. I had become Fong's disciple. The superiority with which he treated me made me feel younger. My eyes moved to The Extraction of the Stone of Madness. It struck me that I wasn't there only because the doctor wanted to beat me at chess. "It's getting dark; you should head home to be on the safe side," he said. The tea had given me a boost. On my way home, the neon ideograms shone brighter and my breathing came easy. Ling wasn't home. I thought about the dive bar where they served booze in candleholder glasses and she hooked up with hysterical men. She took me there once so I would be familiar enough with the place to imagine it. In the back, some colored spotlights formed a Virgin of Guadalupe. At the time, it didn't bother me; now, remembering it, it seems insufferable. The tea was making me feel an uncomfortable vitality. Two or three days later, I looked through her bag when she was in the bathroom. In the case where she stored interchangeable chips, I found the photograph Fong had taken of me. I was surprised she had it. Did she hang onto it out of genuine interest, out of superstition, out of the almost-forgotten custom of making a connection? Ling can't see me how I see myself. I cherished the two moles at the base of her neck and the whitish scar, the size of a grain of rice, that graces her wrist. At night, she stared at me for a long time, as if trying to compare me to the photograph, or imagine me some other way.

4. The ExperimentOne afternoon I went to see Fong and as always we played chess. I remember I had a knight in my hand, it slipped from my fingers, and I suddenly passed out. I came to in a nondescript room, under an irritating light. I looked away and felt pain in my neck. I saw Chucho. Though I didn't hold him in high regard, it was a comfort to find him there. His round silhouette and mild demeanor didn't pose a threat. I saw him touch a portable screen with his fingertips, in a focused, efficient way. Had I suffered an attack? At my age, any fall has consequences. Would I ever walk again? "Chu-cho … " It embarrassed me to call him that, but it was already too late to learn his true name. He came over right away, with a small metal cup: "Water." He helped me sit up. Dr. Fong arrived immediately thereafter, with his enviable light step. He said something to Chucho (he did so in Chinese and I had no idea which of the words he spoke was Chucho's real name), who immediately left the room. Fong sat down beside me: "My assistant is phobic, he can't bear physical contact, but there's no one I trust more to take care of you. How are you?" I felt a mild dizziness and a buzzing in my left ear. I told him so. "It's normal. It'll soon pass. You were in the care of the Indigenous Council for several days." "How long?" "Long enough to finish the treatment. Do you remember it?" "Nothing. Where are we?" "In a safehouse. There's metal in the walls. Electricity from outside can't get in. A true 'Faraday cage,' but I suspect that means nothing to you." "You suspect correctly." In my pocket, I discovered a weaving. It was embroidered with a smiling full moon. It was the complement to the shining sun weaving they'd given me on the basketball court. I remembered what they'd said about dualities on the "playground of the world." The thousand-year-old game of pelota still retained its symbolic meaning. I brought the weaving to my nose. I breathed in the smell of lost fruits, the tremolo of a violin, the faraway touch of a hand. That day, the four indigenous representatives had touched my fingers in a timid way. And yet, I felt how manual labor had softened their palms and left callouses on their fingers. Instinctively, I knew those were the hands that'd cared for me while I was unconscious. With sedulous patience, Dr. Fong told me what had happened. I listened with bewilderment, then with fear—and at last, with the irritated acquiescence with which you accept the inevitable. "Write what happened," he said. It wasn't a suggestion, but an order delivered in a kindly tone. He left the room and came back with a notebook and pen. I don't know how much time I spent in that windowless room. In the back, there was a bathroom with no shower. They brought me meals three times a day, but I stopped keeping track. Fong visited to review information or fill in lapses in the narration. Chucho accompanied me in silence, sunk into his screen. His hypnotic focus led me to believe he had a slight mental disability. In those days I learned that his apparent dullness was the result of a very high degree of specialization. He was creating complex algorithms, according to Fong. The most recent had to do with me. It isn't easy to narrate an autobiographical story someone else recounted for me. "That's part of the experiment," Fong said. "If you tell it well, it'll cease to be an experiment: A successful experiment isn't experimental." I had to overcome the indignation of being in captivity. At 91 years old, I wasn't interested in surrendering my dignity. I merely wanted to see Ling again and my safe passage was the story Fong had asked of me. It all began when she suggested I go to Ciudad Zapata. What she did wasn't a coincidence. For a moment, I gave into the vanity of thinking she'd researched me of her own accord. I guess between her, her uncle, Chucho's computer, and the long memory of the indigenous people, they were able to reconstruct my old activities, my axed occupation, the disordered romantic biography that made me easy prey. I hated having been used. A lingering trace of pride made me believe Ling couldn't have been totally indifferent toward me. The discipline with which she carried out her mission might not be incompatible with taking pleasure in it. I got distracted thinking about this and Fong asked me to focus. With unfeeling objectivity he added, "Experimenting with someone your age is less risky than with a younger person." If the experiment failed, it wouldn't ruin a life, just accelerate a death. If the experiment failed, it wouldn't ruin a life, just accelerate a death. His words conjured confusing images. As he retold it, his story slowly became memories. So were those memories real or induced? In a vague way, like someone looking at out-of-focus realities, I supposed they were mine. Just as I did so, I felt a shiver from another time. After drinking tea in his study, I'd suffered a blackout. I was taken to the village where the representatives of the Indigenous Council interviewed me. Though Fong didn't reveal what herbalism practices I was submitted to, I guessed rue leaves played a role in the disconnection and reconnection of my cerebral circuitry. Since the Founding Hero created the Ministry of Biosecurity, ECOG technology is required to get enrolled in the National Census. Nobody was frightened by having carbon sensors that produce electrocardiograms implanted in them. Locating them is simple, but the cerebral cortex assimilates them in such a way that removing them becomes exceedingly complex. It would've never occurred to me to remove my sensors. I thought about The Extraction of the Stone of Madness in the doctor's studio, and the painting struck me as subversive. The carbon nanoconductors allow us to listen to the Founding Hero's rallies, but most importantly they record our thoughts, habits, and tendencies. It's more what they transmit than what they receive. In a distant time, personal data was gleaned from our cellphones and computers. Today, social DNA is extracted from the source, our brains, a fact both well known and unimportant, because the electrocardiograms create stable patterns of acceptance. It shocks no one. The brain is a transaction. As Fong spoke, Chucho worked on his screen. At some point, the doctor spoke about decision-making. For decades, neurophysiologists had known it wasn't dependent on will, but on electrical impulses: "The brain takes note of the decision after making it." If you control personal information, it's easy to lead people to what they supposedly want. Chucho created algorithms that offered progressively reduced "options." That activity had a paradoxically liberating effect: It saved you from free will. "Choosing is a terrible burden," Fong said, then he added: "The Founding Hero doesn't impose his control: The people conform to the monotony of supporting him. These have been the 'Decades of Happiness,' as he says. The only nonconforming messages are the ones in fortune cookies," he smiled, "because they suggest the possibility of greater happiness. The Founding Hero talks about the chancers and other adversaries so we'll believe that resistance is still possible." He took the screen from Chucho's hands and showed me an incomprehensible diagram: "The 'decisions' you've made in the last 30 years." The graphic seemed sad to me. "You made no mistakes: a model citizen," Fong said, as if he were talking about a silicone mold, one that really disappointed him. Then I remembered that Ling had detected an anomaly in me. During one class, I talked about when vanilla ice cream was yellow. My nostalgia caught her attention. I wasn't demonstrating nonconformity, but I'd remembered something outside the record: a color from another time.

5. The Disorder of the TruthI came to understand the meeting with the indigenous representatives in a different way. They didn't need a copy editor. The motive for the meeting had been something else. They submitted me to a test, offering me the cap of the old political party: The sensors didn't work in that mineral-covered gully and I demonstrated my repudiation. Then they gave me a sombrero with traces of someone else's sweat and I used it without protest. That inspired trust. They handed me an old document; I cut words and adjusted punctuation. Fong paused as he reached this point in our shared story: "What changes most in a writer's work is punctuation; that's where the signs of maturity or old age lie. Who do you think wrote that original text?" An emptiness opened up in my stomach as I recalled the moment I came up with those ideas about justice, the recovery of tribal lands, hope defended from the grassroots. That text came out of an unreal time (2017?) when there were still elections and activism was possible. At the time, I participated in a failed campaign for an indigenous candidate. They hadn't forgotten it. The herbs did their work during the days when I was sedated or awake but unable to remember it. My carbon sensors had been blocked. "You're the first patient of a new illness," Fong said, as if it were good news. He went over to a screen and what happened was terrible. For years, I had heard the Founding Hero's words the way you hear distant murmurs, waves in the sea, buzzing engines, rain falling on the glass of a greenhouse. The image I saw on the screen seemed recent, but the origin of those words was remote and precise: I had written them. I remembered being in the office where I served my sentence for being a "failed writer" (forgive me the well-known pleonasm). By night, I wrote texts that were deemed subversive; by day, I composed pompous speeches so the Founding Hero could say the same thing without consequences. My nocturnal writing was a protest against the uselessness of my daytime writing. I was in the service of both the rebellion and the demagogy. I was a critic of power, but helped perpetuate it writing formulas that banalized radicality. "You've got to make a living somehow," friends familiar with my work as ghostwriter said sarcastically. The worst part was that my motives weren't strictly financial. I actually thought the indigenous people would never achieve change from below. I wanted to influence the government's peaceful reforms and was awaiting my moment of vainglory: The Founding Hero, who listened to no one, would listen to me. Was it worth it to belatedly remember this error? I hated that Fong was submitting me to this torture and I asked him to leave me in peace. "At 91 years old, you can still start something," he teased my vanity. "There's injustice and violence, but nobody cares. People live in satisfied submission," and with the severity with which he moved a bishop on the chessboard, he added: "Submission is an algorithm. That's why we decided to infect you; error is your cure." I hated that I'd drank his tea. Reality laid bare not only seemed unbearable: I had helped create it. "And you, what do you gain?" At last I asked the decisive question. Maybe he was thinking of Confucius when he said: "I don't want revenge. I work with the greatest wealth on the planet: trash, human waste. An increasing number of the world's bodies end up here. The United States never realized that when they entrusted China with the control of their waste. We extract the nanoconductors with personal data on them and turn the bodies to ash. We keep the information. We have the greatest repository of human data in history, something colossal, don't you think? Every civilization is known by its funeral rites," he paused. "Coincidence brought me here. My country agreed to sully itself with foreign waste and your country resigned itself to being waste, but maybe it's not too late to change things a little. Write, my friend, write your story." "Nobody reads stories anymore." "Take a risk: We can't forget the future." "Things that cause us pain are of great value." He explained how patients suffering amnesia can't guess what will happen the next day. Eliminating the past prevents projecting into the future. As a patient, I was the opposite. I was engaging in an archaic practice that helped to imagine what was to come. I remembered the Huichol painting in his studio and the way he pulled back the curtain to reveal it. "A patient was cured by looking at it," he'd said. I asked him about it. "I hoped we would come to this. When we were building the plant, I suffered an accident. The place where the engines now rumble was an infinite garden, a branch of paradise. It was sad to see how the excavators destroyed the gardens. The destruction of thousands of fruit trees filled the air with the smell of citrus, sludge, and gasoline. Someone told me there were still orange trees on one hill and I went there. I wanted to see something that would be lost forever. I was so relaxed I didn't notice a drop and I fell over a cliff. I was rescued by the indigenous people you met on the basketball court. They saved my life, but also made me drink herbal infusions that gave me back the singularity, the defects I'd suppressed. We learn from our mistakes, as I said already. We have to save that: the 'human factor.' " "So, I'm not the first patient, you are." "In a certain way I was. I was delirious for days, in front of the painting that's now in my studio, thinking those arabesques were reality, until I realized they represented the poison I'd sucked out of reality. The interesting thing is it's a beautiful poison. Things that cause us pain are of great value. It doesn't matter who Patient Zero is. You must write your story. Don't worry about the errors: We depend on them. You've had a long life; you can write with the perspective of a person who has passed through many modes of punctuation." "And you?" "I don't tell stories, my friend. My errors are technical; yours are of another kind. Write: Make mistakes. Avoid qualification: Error is invaluable." For a moment, I feared Fong wanted to incriminate me with my confession, but I believe he had other motives. I need to believe it. His rebellion has a scientific basis. I know how he plays chess: For him, the rules are useful if they provide a stimulus. Now he is seeking other rules for dealing with reality. Maybe Chucho is designing a diagram that summarizes the complex network of resistance that's thriving among the original peoples, the old Chinese immigrants, and those individuals who alter their carbon conductors and return to a contradictory reality, thanks to almost-forgotten herbs, the tea of thick consistency I drank in Fong's company. I've convinced myself he drinks the same substance. I want to believe the clandestine work he carries out while grinding up tons of waste obeys a principal that until recently would've seemed illogical to me: He saved millions from the animal contagion in the "times of the hecatomb" and now he's taken on the greater challenge of saving us from ourselves. My own motives are clear: I long for uncertainty, what in previous times was called "literature." I supposed Fong will include these pages in the data collected from the trash. I don't know the scope of his strategy, because I've only been its tool. It comforts me to know that my contribution wasn't entirely imposed on me, that I was guided by a personal conviction. A woman took interest in me because I spoke of the bygone color of vanilla. I remembered that before leaving for the chess game when I lost consciousness, I ran into Ling in the kitchen of the bungalow. When she saw me, she hurriedly put something away. We talked for a while and then she went to her room. On the table I saw scraps of tea leaves. I brought them to my nose and breathed in the smell of the substance Dr. Fong has been giving me. Ling also sought irregularity. I see her silhouette, outlined against the dense and reddish sky of Ciudad Zapata, and imagine a future for her, a future I'll never see: Ling reads this line and understands; she accepts the disorder of the truth (the exception and the error); she finds a way to feel and, maybe, to love. Read a response essay from Adam Minter, author of Junkyard Planet: Travels in the Billion-Dollar Trash Trade. More From Future Tense Fiction And read 14 more Future Tense Fiction tales in our anthology, Future Tense Fiction: Stories of Tomorrow. Future Tense is a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University that examines emerging technologies, public policy, and society. |

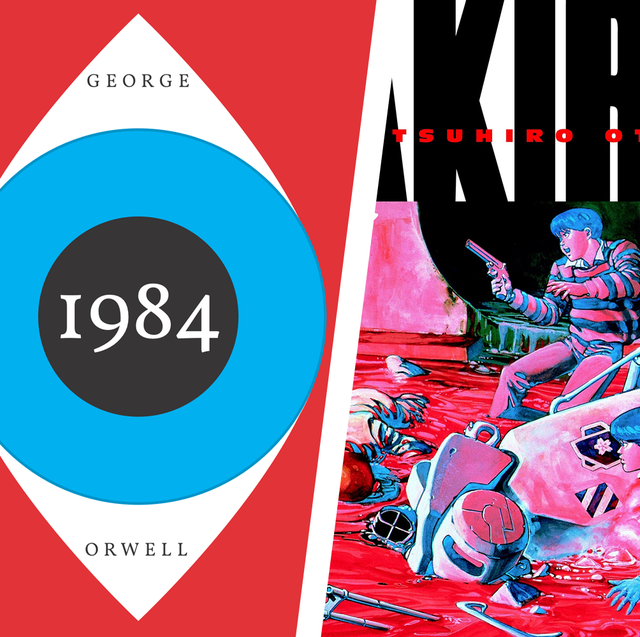

| 23 Best Sci-Fi Books of All Time - Science Fiction Novels - menshealth.com Posted: 23 Apr 2020 09:49 AM PDT  Amazon Defining "science fiction" (so that one can say, definitively, this book is a sci-fi book) is a little like defining "spiritual" or some other vague belief category that includes so many contradictory and peripheral and quasi-mystical tenants and offshoots that your friend who swears by it probably has no idea what it really is. "Sci-fi" is a term that says everything and nothing simultaneously. We know what it means, intuitively, but not so much definitionally. It involves, we think, kombucha. Some works that seem obviously sci-fi (like Star Wars) are really not (Star Wars is a space western inspired by myth and samurai films, damnit. Fight us.) While other works that seem far from sci-fi (the early nineteenth-century's Frankenstein, for instance) are the genre's very DNA. At its core, science fiction is a conceit. It's a thought experiment beginning with a "what if X" or an "imagine a world in which Y." It has something we might call a Device. And the Device cannot be peripheral, some incidental feature of the world. No, the narrative must turn upon this make-believe conceit. It must be its axis, it's inciting incident, its reason for existence. The story cannot be the story without the Device. (You might then say, well isn't "the Force" this Device? Or is more of a "power," closer to the superhero genre. But would you not call something like X-Men science-fiction? Yes? You can see how tricky this becomes.) The Device can be both a Thing or an Event. And so works centered on some "extinction-like event"—books like The Road, or The Handmaid's Tale, or The Leftovers—do, in effect, count as science-fiction. (Though, we've included far less of this type of sci-f, what we'll call "naturalistic sci-fi," versus other, more traditional tech-driven sub-genres.) And while loosening the sci-fi definition may open up just about the entire library, we've narrowed a list down to (in no particular order) some amazing reads. Here are the best sci-fi books for all readers, whether you haven't touched a book since high school or you daily burn incense to the alter of Arthur C. Clarke. Advertisement - Continue Reading Below Advertisement - Continue Reading Below |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "famous short story,short stories for high school" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment