The Best Books You’ve Never Heard of (Summer 2020) - Book Riot

The Best Books You’ve Never Heard of (Summer 2020) - Book Riot |

- The Best Books You’ve Never Heard of (Summer 2020) - Book Riot

- “Shirley”: A fictionalized account of writer Shirley Jackson's life - WSWS

- Petoskey woman was bothered by Hemingway's portrayal of her the rest of her life - Petoskey News-Review

- 32 Short Story Collections That Will Cure Even The Worst Reading Slump - BuzzFeed News

| The Best Books You’ve Never Heard of (Summer 2020) - Book Riot Posted: 29 Jul 2020 03:41 AM PDT Being immersed in the book world often means feeling you're drinking from a fire hose of new releases. Every week brings more fodder for the TBR pile, and it seems like everyone is talking about that book you haven't gotten to yet. Trying to keep up can be exhausting. Of course, there are plenty of new and popular books that live up to the hype, and it can be fun to read what everyone else is reading so that you can discuss it at length—but those aren't the only books worth reading. Not every book has a big marketing budget, and some amazing books get released into the world with very little fanfare. The Best Books You've Never Heard of series shines a spotlight on books that don't get the attention they deserve. This is where we step back from the nonstop race to read the books of the moment, and instead give some attention to books that we don't hear a lot of people talking about. Our entirely arbitrary cut off for this is books that have 250 or fewer Goodreads ratings—you can find out your own little-known gems by sorting your Goodreads Read shelf by "num. ratings"! But enough prelude: let's get into the books!  Girl of Flesh and Metal by Alicia EllisAt first, I wasn't sure what to think of this book. I love both YA and science fiction and while the blurb I read made me interested, I was nervous I'd be disappointed—but I wasn't! This YA follows a teen girl named Lena whose parents are the owners of CyberCorp—the leading corporation in all things tech. On one hand, Lena enjoys the privileges of being the well-known and somewhat popular kid with her own crew, but her life changes after a near fatal accident and she's now sporting an AI arm. She feels like a freak and her friends are now scared of her. Things take a turn for the worse when anti-technology activists start protesting and becoming more aggressive against Lena's family. Lena starts sleepwalking and the following day learns that her friend was murdered. Eventually, Lena starts looking like a suspect and she has to do everything she can to prove her innocent or admit she's turned into a murder. —Erika Hardison  In the Silences by Rachel GoldAs many white people are starting a long-overdue education in whiteness and anti-racism, In the Silences is a great book to turn to. This is a YA novel equally about Kaz's exploration of their nonbinary identity and their awakening to how racism affects their best friend (and love interest), Aisha, who is Black and bisexual. I loved how both Aisha and Kaz educate themselves to be better allies to each other—they support each other while recognizing that their struggles are different. What Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness does for small children, In the Silences does for teens and preteens. They both explain that it is white people's responsibility to learn about racism and fight to change it, and especially to educate each other. For both the nonbinary rep and the exploration of whiteness, this is a perfect addition to any high school library or teen's bookshelf. —Danika Ellis  Moonshot: The Indigenous Comics Collection, Volume 2 edited by Hope NicholsonMoonshot is a series of indigenous comic anthologies. The first volume looked at the future, with sci-fi and fantasy stories. This volume examines the present, and each story is an own voices look at the author's nation/community. One of the things I appreciated in both volumes is the range of art styles at play. Some are bright and simple, others complex and using dark tones. There are some names I know and love included, like Darcie Little Badger (if you haven't read her F/F story about taking care of puppies in a spaceship in Love Beyond Space and Time, what are you doing?), Daniel Heath Justice (whose "The Boys Who Became Hummingbirds" is about a two-spirit boy), and Richard Van Camp. I used one of these stories to teach comics in a high school English class, and I think this is a great book to teach from. —Danika Ellis  Talk Like A Man by Nisi ShawlI've never really read a science fiction or fantasy novel that embraces Yoruba religions like Ifa into a fantasy short story that's not mocking or making light of the practice. In Talk Like A Man, there are only a few short stories, but it almost feels like a biography of how they arrived in the headspace to combine African religion, fantasy, horror and science fiction all together. My favorite story is "Woman of the Doll" because it involves a woman, a doll, a cult and a worshipping altar. There's also a mini lecture in the book to help readers understand Ifa more. —Erika Hardison  Wain: LGBT Reimaginings of Scottish Folktales by Rachel PlummerWain is a beautifully illustrated poetry collection, drawing on Scottish myths and legends and reinterpreting them through an LGBT lens. A nonbinary Nessie, a kelpie that can see the truth of everyone's gender, and two werewolf husbands are some of the characters you'll meet within the pages. Although the collection is aimed at children, it's a great read for poetry lovers of all ages. Reinterpretations of myths and legends are something I have a weakness for at the best of times, and Wain is an especially skillful example, drawing together the ancient and the modern in short snippets of legends that will draw you into a rich mythical world. —Alice Nuttall  How Poetry Can Change Your Heart by Andrea Gibson and Megan FalleyIf you love poetry, this is a great book to celebrate your love with. If you are just starting out, this book can introduce you to the world of poetry by making you notice all the ways it breathes in the world around you. It's heartwarming, witty, smart and underrated. It encourages you to let go of preconceived notions and appreciate poetry in all its unpredictable glory! —Yashvi Peeti  The Water Thief by Claire HajajWritten through the eyes of a British man who goes to a remote village at the edge of the Sahara to atone for his own guilt, The Water Thief is, surprisingly, not a story of redemption. Rather, it explores how journeys like these are not about those who make the journey, no matter how selfish their motives. Nick's developing relationships with the family he lives with have their ups and downs, and while not everyone has a happy ending, it brings about a sense of peace that seems far more important. —Anmol Irfan  In the Company of Strangers by Awais KhanI particularly loved Khan's book because he managed to write his female South Asian characters as people who actually exist. While that seems easy enough, female representation in South Asian media is heavily polarised, so In the Company of Strangers brought a refreshing change. Even in their flaws, his characters maintain their relatability—particularly Mona. The book also touches upon some sensitive topics but manages to do so while maintaining its gripping tone and appearance of everyday life in Lahore. —Anmol Irfan  Pickup Notes by Jane LebakFirst and foremost, the main character in this book is a violist. Which is just awesome in and of itself. Why? Because violists are awesome! On a serious note, I really enjoyed this story about a musician whose life wasn't, if you'll pardon the pun, playing out the way she wanted. She was the black sheep in her family because of her love of the viola, even though it gave her a close relationship with her deceased grandfather. Her string quartet finds themselves in the spotlight of the wedding community when the second violinist rips a guitar riff at a ceremony. And it changes them all in various ways. Her family is dysfunctional and seems to have no use for her apart from whatever she can do for them, and her sister is a real piece of work. So if that is a button for you, please be aware of that going in. Her string quartet family is also dysfunctional, but at least they generally care about her. It is a great book that not a lot of people have read, which is a shame, but it is one that truly is amazing and will give you a nice warm feeling, especially if you have a background in music. —PN Hinton  The Unrepentant by E.A. AymarAfter running away from an abusive home, Charlotte is kidnapped and sex trafficked by a dangerous group of men, including a dirty cop. She manages to escape with the help of a stranger. But as the men try to find and kill her, knowing that the police can't be trusted to help, Charlotte realizes her only chance at survival is stopping her captors herself. This story is dark and dangerous and tense. Obviously the subject matter here is very heavy (TW for rape, kidnapping, child sex abuse, physical abuse, violence), but I really appreciate that Aymar was upfront about the research he did on sex trafficking. He takes this issue seriously; it's not just used as a thrilling plot device. Charlotte's character is multifaceted and well thought out, and her journey kept me on the edge of my seat. —Susie Dumond  The Museum of Whales You Will Never See by A. Kendra GreeneI've only just started this book, but I can already tell it's going to be one I tell all my friends and family about. As a person who once went to a Mythic Creatures exhibition at a museum and thoroughly enjoyed the weird mythology and folklore behind ancient mythic creatures, this book was instantly a hit with me. Iceland has more than 265 museums—nearly one museum for every ten people in the country! And many are weirdly specific and strange, which makes me want to visit that much more. From a museum of sorcery to a museum of phallological specimens (it collects penises from every known mammal in Iceland), this strange and bizarre book is not only incredibly fascinating, it's also a beautiful book, perfect for gifting to loved ones and telling them all about the weird museum filled with penises. —Cassie Gutman  Snapdragon by Kilby BladesA no-strings arrangement of companionship and sex turns into true love in Kilby Blades's highly original, genuinely unconventional, feminist and romantic debut. When Michael and Darby meet, the chemistry is palpable, but so is the mutual admiration and genuine respect. They enter into a mutually beneficial agreement rather than a relationship, not because something is missing but because they both have high-powered careers that demand their full attention and want to protect what they have. Despite the ground rules, their searingly hot connection quickly becomes a soul-deep one. Though Blades is playing in a familiar sandbox with the arrangement trope, that's just a jumping off point for a complex and emotional story packed with surprises and suspense. The writing is gorgeous, and Blades plays with deeper issues of identity as well. I've read it twice so far and I'm looking forward to reading this one again. Snapdragon is the first part of a two book duet so the happy ending arrives in book two, Chrysalis. —Carole V. Bell And there you have it, 12 amazing books that deserve more attention! How many had you heard of? And what are your favorite books that have under 250 Goodreads ratings? If you can't get enough hidden gems of the book world, check out our previous editions of the Best Books You've Never Heard of! |

| “Shirley”: A fictionalized account of writer Shirley Jackson's life - WSWS Posted: 28 Jul 2020 10:16 PM PDT Shirley: A fictionalized account of writer Shirley Jackson's lifeBy David Walsh |

| Posted: 24 Jul 2020 10:57 AM PDT  In the second decade of the 20th Century, a young lady in Northern Michigan befriended an aspiring writer who summered near her Petoskey home. Her name was Marjorie Bump. His was Ernest Hemingway. She was 18 when he was 20. Their time together was fleeting and it's unclear if it can be properly termed a romance. But a century later, the two remained joined forever in the pages of two Hemingway short stories, where he mentions her by name. Therein lies the problem. Bump never consented to being a character in the stories. She was not thrilled with how she came off, fearing readers would conclude she'd had an affair with the famous novelist. Hemingway's words were read by millions and prompted all manner of gossip. A group of West Bloomfield High School students is helping to make Bump's account heard. "Marjorie Bump got a bum wrap," said Jennifer McQuillan, a board member of the Michigan Hemingway Society, who teaches English at West Bloomfield. "Because her name was Marjorie Bump, you can imagine what they did with Bump. They slut-shamed her. Her daughter spent a lot of time trying to clear up her reputation. It was so painful for Marjorie. As Hemingway rose in fame, the interest in Marjorie rose as well. It was insufferable, especially when people got the wrong idea." Bump, who died in 1987, vented about the relationship in a lengthy private correspondence with a New Hampshire bookseller. Those letters, some handwritten, others typed, now belong to the Michigan Hemingway Society. McQuillan has enlisted students in her 12th-grade college prep course class called Points of View to help transcribe them into a digital format for research purposes. Some of the letters have been published before. In 2010, Bump's daughter, Georgianna Bump, included some of them in a book "Pip Pip to Hemingway in Something from Marge," that also includes other reflections from her mother about Hemingway. Efforts to reach the daughter were unsuccessful. McQuillan said the transcription project will expand on that work by providing researchers with the complete set of letters. McQuillan also used the letters to prompt a discussion about reputation damage, something students today encounter on social media. "If Hemingway has controlled her reputation this long, look at how fast you can shape someone's identity with just a hashtag," McQuillan said. "How do you protect yourself form being a tag? How do you control your identity in a world where you can have that all undone in a click?" Nick Adams storiesHemingway mentions Bump in two of his Nick Adams stories, "The End of Something," where she's identified as Marjorie; and "The Three-Day Blow," where she's Marge. Nick Adams is considered Hemingway's alter ego. In "The End of Something," Adams and Marjorie share what appears to be shaping up as a romantic encounter. The pair is out fishing in the evening. Then they come ashore for a fresh perch dinner beside the moonlit water. Adams takes the occasion to break up with Marjorie and she rows away in a boat, alone. The break up is mentioned again in "The Three-Day Blow," when Adams's friend, Bill, tells him it was the right thing to do. When the stories were published in 1925, Petoskey was still a small town. Bump's father ran a hardware store there and it didn't take much sleuthing for the locals to identify Marjorie. She left Petoskey and lived most of her life in Florida. The portrayal of her in the stories bothered Bump to her death. When she was buried in her hometown, her gravestone was engraved Lucy Bump Main. Though she always went by her middle name of Marjorie, her first name was Lucy. Her married name was Main. Strong womanNot everyone thought Bump came off badly in the stories, said Linda Patterson Miller, a Hemingway scholar who teaches English at Pennsylvania State University's Abington campus. "I think she should be quite pleased actually," Miller said. "The portrayal of her is quite beautiful. She's one of Hemingway's strong women. She has such dignity in not making a fuss when Nick Adams says that love is not fun anymore." Miller said many of her female students admire Bump's character. Miller said she doubts Hemingway and Bump were lovers, but a summertime romance seems likely. She suspects Bump's real displeasure may stem from the way her family, particularly her mother, was portrayed. In "The Three-Day Blow," Adam's friend, Bill, derides Marjorie's mother as bossy and implies a class distinction, telling Adams that Marjorie "can go marry somebody of her own sort..." "She actually comes across as a strong woman, but apparently, people in town talked, according to Marjorie," Miller said. "She felt her reputation was besmirched by the stories and the reference to her actual name." Marjorie isn't the only Hemingway friend to object to being mentioned in his work, Miller said. When Hemingway wrote "The Snows of Kilmanjaro" for Esquire magazine, he included a reference to "Poor Scott Fitzgerald," who was in awe of the rich. The famous author of "The Great Gatsby," F. Scott Fitzgerald, a Hemingway friend from their Paris days, was so irked by the mention he prevailed on the editor, Max Perkins, who convinced Hemingway to delete it before the story was published as a book. McQuillan's students embraced the transcription task. Because the school was closed by COVID-19, McQuillan sent them digital scans of the letters. The originals now are housed at the Clark Historical Library at Central Michigan University. The students then transcribed them precisely, including typos and misspellings as well as information on the envelopes in which they were mailed. An editor reviews their work for accuracy. "It is such a rare opportunity for high school students to be working with primary source documents," McQuillan said. "This was a gift." The letters are correspondence Bump traded with a New Hampshire bookseller, Donald St. John, beginning in 1966. After Hemingway committed suicide in 1961, St. John set out to interview people who had known the author in life. He tracked down Bump, who by then was married to a Daytona Beach dentist, Sidney Main. St. John peppered her with questions about Hemingway. She responded at length on some occasions and tersely at other times. In one typewritten letter from January 1967, Bump described her and Hemingway as sharing a friendship and she denied having an affair with him. She wrote to St. John at that age, she had no "knowledge or interest in sex." She also urged him to not consider "The End of Something" as a true story, noting Hemingway visited her years later in Florida and the two corresponded for years. Before she died, Bump destroyed her exchanges with Hemingway. But through the letters she wrote to St. John, students said a more complete picture of both Bump and Hemingway emerges. "In Hemingway's short stories that she's in, she was always depicted as someone who was cold and kind of selfish and just kind of superficial,' said Sydney Carroll, one of McQuillan's students who graduated this year and will study psychology at Wayne State University in Detroit in the fall. "But through the letters, you just see a whole different side of her, that she had passions of her own. She wanted to be a writer herself. She loved writing." Carroll is 18 now, about the same age Bump was when she was close to Hemingway. Carroll said she has transcribed about eight letters. There are about 250 of them in the collection and the work is ongoing. "She talked about how her life was affected by the things Hemingway said about her and how she didn't like how she was depicted and how she felt he treated her unfairly and wrote about her own unfairly," Carroll said. Carroll said that one lesson she draws from the letters is to define yourself, rather than let others define you. "You can only control what you do and what you say," Carroll said. "You shouldn't let the words of others, ultimately have so much effect on who you are, what you accomplish and the legacy you leave behind. You're in control of your legacy and your identity and the name you make for yourself." Learning cursiveJarrett Hazelton is another student who worked on the project. One challenge he had to overcome was reading the cursive handwriting Bump used in some of the letters. He'd learned some cursive in early elementary school and his parents helped him, too. "I learned that she's an eloquent writer and she's quite the intellectual person," said Hazelton, who graduated from high school this year and will study at the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music. Some critics have tagged Hemingway as a misogynist and McQuillan notes he had "four marriages and umpteen girlfriends." But Hazelton said despite Bump's misgivings about how Hemingway portrayed her in print, she defended him on that count. Hazelton said although some of Hemingway's stories tend to portray him as a misogynistic person, Bump described him more positively in her letters. "I see her as a very trustworthy person and I'm seeing that she's giving another side of the story," Hazelton said. Filling gapsPenn State is in the process of compiling and publishing Hemingway's letters. The school has access to more than 6,000 letters that survive. The work the students are doing on the Bump letters is important because it fills in some gaps in Hemingway's correspondence, said Christopher Struble, president of the Michigan Hemingway Society. "There are still little holes in the Hemingway story," said Struble, a Petoskey jeweler. "This may seem trivial, but Hemingway comes up here in 1919 to begin his career as a professional writer of fiction. Well we knew he was here. We know we've got letters back and forth from his family. But he disappears at Christmastime. So where was Hemingway in Christmas 1919?" The answer is found, Struble said, in the Bump's correspondence with St. John, where she recounts a conversation she had with Hemingway. "He talks to Marge Bump and he tells her, 'you know if I could spend every Christmas of my life like that Christmas 1919 in Petoskey, that would be great. I'd be a happy man,'" Struble said. "So there's really heartwarming stuff in these letters and it just gives us a little bit more provenance and fills in a couple gaps that even Penn State wasn't able to find." McQuillan said the exercise has been a good learning experience for her students. "I still have kids working on this over the summer for community service hours and some of my seniors wanted to continue because they felt so invested in the project," she said. "They were determined to give Marjorie a voice." |

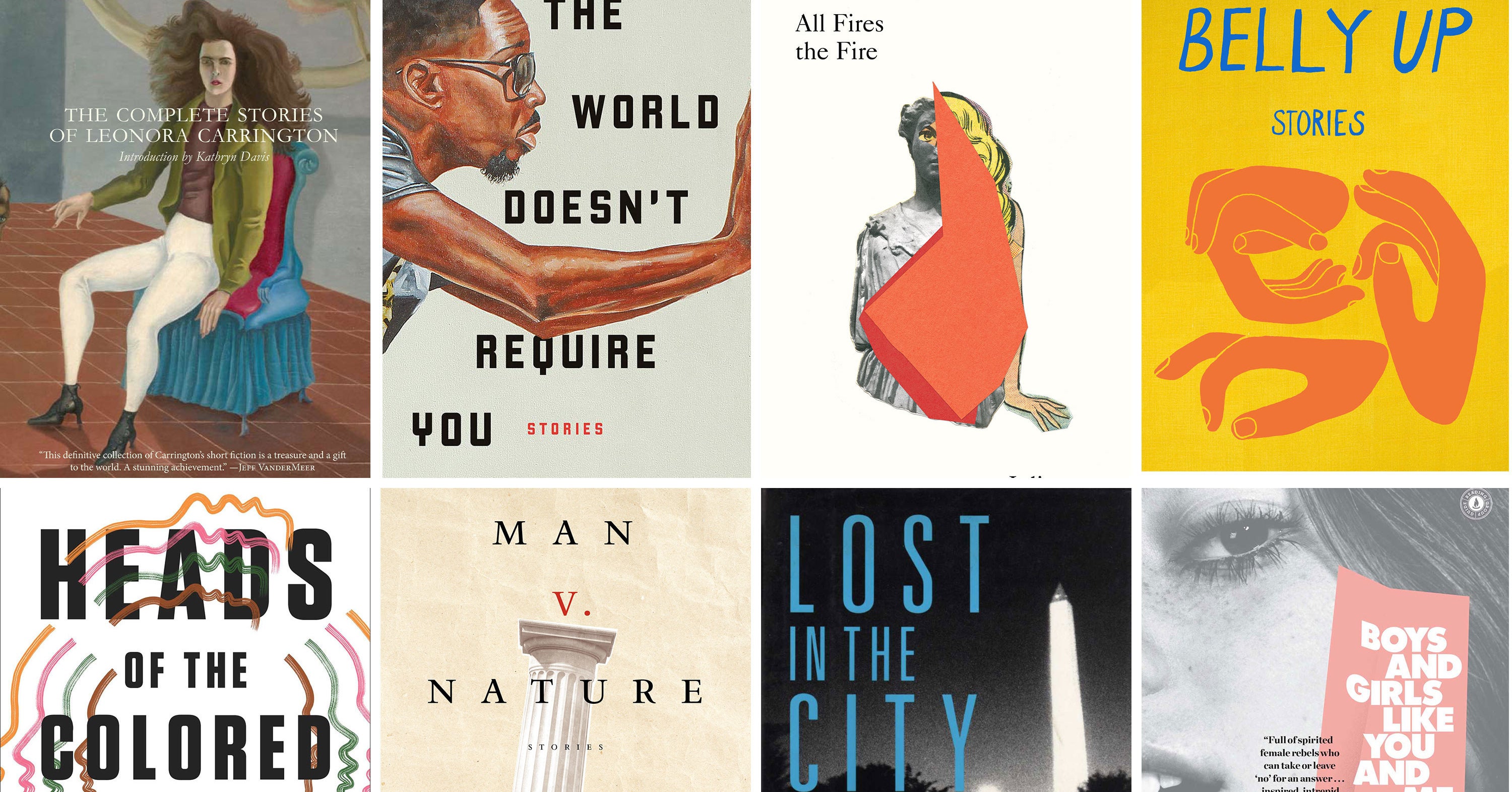

| 32 Short Story Collections That Will Cure Even The Worst Reading Slump - BuzzFeed News Posted: 29 Apr 2020 12:00 AM PDT  Dorothy Project, Liveright, New Directions, Strange Object, Scribner, Amistad Press, Harper Perennial, 37 Ink I picked up this collection back in 2017 due entirely to the cover — the portrait of a wild-haired woman, the Jeff VanderMeer blurb ("This definitive collection ... is a treasure and a gift to the world."). Now it's a book I regularly recommend as an all-time favorite. Carrington was a key creator in the Surrealist movement; her art and stories imagined beautiful, monstrous, and unwieldy worlds full of strange creatures and discomfiting interactions, often representative of her own mental illness. (Carrington was unwillingly admitted into a mental institution after a psychotic break during World War II, which she describes in the equally fantastic Down Below.) If you have a high threshold for weird — and/or if you loved Her Body and Other Parties — you should give this collection a try. —Arianna Rebolini The stories in The World Doesn't Require You all take place in the fictional town of Cross River, Maryland, built by the leaders of the country's only successful slave revolt. Each story follows different enchanting residents — a struggling musician who is also the last son of God, a PhD candidate whose dissertation unwittingly sparks chaos, a robot; as a whole, the collection weaves incisive criticism, dark humor, and magical realism in profound explorations of belief, love, justice, and violence. —A.R. The late Argentine writer Julio Cortázar is celebrated as a groundbreaking figure in Hispanic fiction for his use of the fantastical and his rejection of conventional narrative structure. This collection, originally published in 1966, makes clear why he's so beloved. It opens with "The Southern Thruway" — a story about a traffic jam outside of Paris that ends up lasting for weeks, giving rise to ad hoc survival committees and alliances — and then jumps through space and time, from Cuban revolutionaries to Roman gladiators to a flight attendant obsessed with Greece. Each story is more compelling than the last — and if you think you know where any one is headed, you're probably wrong. —A.R. Belly Up by Rita BullwinkelBelly Up is an astounding collection of short stories — stories about girls who want to be plants, or a living boy who grew up in a family of zombies, or a dying woman who sneaks out for a night swim with an ailing man. These stories exist in worlds just past reality, just slightly uncomfortable, familiar until, suddenly, they aren't. And I didn't just read these stories, each revealing at once the absolute absurdity and magnificence of being alive; I savored them. Bullwinkel's writing and world-building demand space to reflect on it, react to it, and then, if you're like me, shout about it to anyone who will listen. —A.R. Putting together this list, I'm realizing I have something of a ~type~ when it comes to short stories — in a word, weird. This one is an entirely different flavor, no less delicious. These stories focus (in spite of the title) almost entirely on women and girls navigating all manner of relationships — a 9-year-old girl and her father's new girlfriend escaping an uncomfortable birthday party; a young woman having an affair with her married boss — and Kyle depicts their desire, cruelty, and insecurity with heartbreaking clarity. —A.R. Though perhaps best known for his Pulitzer Prize–winning novel The Known World, this 1992 story collection first put Jones on the map. Set in Washington, DC, back when it was known as Chocolate City, Jones's stories feel vaguely folkloric in nature, even though they are about ordinary black folks, from a girl who is given a flock of pigeons to care for to a mother living in the house her drug-dealing son bought her. Suffused with a quiet sadness, these stories linger with you long after you're done reading. —Tomi Obaro In a collection of short stories about all of the ways we define survival, Cook creates slightly off-kilter realities and the otherwise unremarkable characters who inhabit them — a miserly neighbor in a post-flood dystopia, 11-year-old boys who have been declared "not-needed," a young woman whose house is swarmed after a span of good luck. It's grim, violent, and darkly funny, but never so far removed from our most human urges to seem totally implausible. —A.R. Thompson-Spires' debut collection is a fearless exploration of race, identity, and class. The stories touch on the ways spaces and circumstances are coded (in one, a young girl tries to learn to be "more black" as a way to make up for her family's upper-middle-class standing); Thompson-Spires deftly grapples with the pressures of being black in a country built around and for whiteness. It's sharp, potent, and deeply felt. —A.R. Read "A Conversation About Bread" from Heads of the Colored People. Riverhead, Catapult, Graywolf, Vintage, Lenny, 2040 Books, Small Beer Press, FSG A woman creates a sentient child out of hair trimmings. A rebellious high school senior living in the US is sent back home to Nigeria to live with relatives, where family secrets are unearthed. A woman with the ability to take people's grief away grapples with the limits of her powers in a futuristic alternate universe devastated by climate change and war. The stories in this excellent 2017 collection are a mix of different genres — fantasy, realism, science fiction. What unites them is Arimah's confident, innovative storytelling. Each story packs an emotional wallop. —T.O. Arndt's debut short story collection is provocative and haunting, forcing readers to reckon with their assumptions around gender and identity, masculinity and femininity, conformity, and queerness. Her narrators — each speaking in a frustrated but often hypnotic first person — travel through worlds that demand they subscribe to a system of categorization that simply doesn't work for them; each story shows the internal and external manifestations of this conflict. There's the parasite infecting a couple whose relationship is falling apart, the crystal cave one narrator refuses to leave, the beast that shows up nightly in the bedroom of another. It's about the awkward absurdity of bodies, and Arndt is masterful in describing it with metaphor and ambiguity. —A.R. Set predominantly in '90s Brooklyn and the Bronx, A Lucky Man recognizes the stories to be told in banal disappointments — a failed marriage, a sick mother, an unrequited crush. Brinkley is a marvelous writer. The jaw of a man without his dentures looks like "a rotten piece of fruit." There's a solemn beauty to his writing, a clear sympathy for his characters, all of whom are vividly rendered. —T.O. Tobias Wolff, along with writers like Raymond Carver, ZZ Packer, and Andre Dubus, is partly responsible for the 21st-century renaissance of the short story (though he'd probably disagree with a word so strong as 'renaissance'). The Night in Question is his third collection, one of many remarkable works of his; Wolff is also a killer memoirist. What I love about Tobias Wolff is his intimate portraits of family life set against terrifying and complex macro backdrops, from wars to great sweeps of generational change. He's got a deceptively simple style that, combined with his incredible talent at character development over just a few small pages, has often brought me to tears. I'll be revisiting his work in lockdown; these are stories that make you believe in a life fully lived. —Shannon Keating Zhang's debut story collection is at once explicit and poignant, vulgar, and refined — equal parts pain and beauty. Each story centers a young, first-generation Chinese American woman narrator, each with a distinct voice but overlapping in experience (most show up in each other's stories) and linked by the loyalty, guilt, and love that comes with knowing how much, and how continuously, one's parents have sacrificed. The weight of these conflicting emotions pulls on Zhang's narrators and her writing, often in accelerating run-on sentences — but the headiness is balanced by Zhang's incorporation of the (often grotesque) physical realities of being a human being. It'll make you laugh, it'll make you cry, it'll make you gag, but you'll love all of it. —A.R. Chau's exhilarating debut probes the lives of second-generation Chinese American women, especially focused on dating and sex — their disruptive hookups, tiring long-term relationships, their search for something meaningful. Throughout, Chau writes sexuality in a way both vivid and new (see: "Pants and skirts were shrugged, scooted down, buttonholes were stretched into O's like gasping mouths, then relieved of their charges"), and her stories are honest and arresting. All Roads Lead to Blood will ring true to anyone who feels like they're lingering on the path toward figuring themselves out. —A.R. Pinsker's debut short story collection is speculative and strange, exploring such wide-ranging scenarios as a young man receiving a prosthetic arm with its own sense of identity, a family welcoming an AI replicate of their late Bubbe into their home, and an 18th-century seaport town trying to survive a visit by a pair of sirens — all while connecting them in a book that feels cohesive. The stories are insightful, funny, and imaginative, diving into the ways humans might invite technology into their relationships. —A.R. Samantha Hunt's stories are about metamorphosis — physical, psychological, fantastical, life-changing. There's the FBI agent who ruins his own mission by falling in love with a military robot; the woman who can't stop cheating on her husband every time she shifts into a deer; the wife who, after months of no sex, starts to wonder if her husband is even real. Hunt writes about women's relationships to their bodies and their realities, their trust in themselves, and she does so with such sharp writing, and within such beguiling worlds, that The Dark Dark becomes impossible to put down. —A.R. Vintage, Riverhead, A Public Space, Coffee House Press, FSG This collection wasn't on my radar until I saw (and became obsessed with) the 2018 movie Burning and found out it was based on "Barn Burning" — a short story in a Murakami book I'd somehow never read. Luckily I fixed that problem. The 17 stories in The Elephant Vanishes are imaginative, eerie, provocative, and sardonic; they follow a woman who hasn't slept in 17 days, another who's courted by a monster in her backyard, a couple who decide to rob a McDonald's, to name a few. It's everything we love about Murakami, in bite-size pieces. —A.R. Lorrie Moore, whose (also excellent) early work inspired a generation of young writers to abuse the second person, is a veritable master of the short story. Her third collection, Birds of America, is arguably her best, but you wouldn't go wrong if you were to pick up her full collected stories, published in 2020. What's so compelling about Moore's work — besides her sometimes lyrical, sometimes straightforward, but always gorgeous prose — is that she manages to make you laugh and make you completely, existentially devastated in the span of a single paragraph. Her stories are, to borrow a name of one of her collections, Like Life: miserable, hilarious, morally ambiguous, lovely, mundane, profound. —S.K. For the inaugural title of their new book publishing imprint, literary magazine A Public Space released Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, a collection of the late Bette Howland's autobiographical short stories spanning the entirety of her career. Howland's writing — notably lauded by Saul Bellow — is rich with wry observations and humility, drawing from her experiences as a self-identified outsider: a divorcé and single mother whose family disapproved of her; a writer and artist fighting poverty, self-doubt, and mental illness in working-class Chicago. —A.R. Lot by Bryan WashingtonWashington's debut short story collection is an ode to Houston and a vibrant portrait of the myriad people who call it home. The stories circle around a young boy figuring out his sexual identity while holding down a job at his family restaurant; around him, a city of creators, survivors, and hustlers vibrates with life. Washington's effervescent prose draws the reader into the fold — his use of first person, especially plural first, can read like a generous inclusion — as his characters explore family, community, new freedoms, and love. It's hard to talk about short stories without bringing up Flannery O'Connor — one of the truly great American short-story writers of the 20th century. Her works are dark and disturbing commentaries on ethics in Middle America as she weaves grotesqueries out of the traditional "moral at the end" short stories that are typical of the genre. The Complete Stories, for which O'Connor posthumously won the National Book Award, is a great intro to some of O'Connor's most famous stories and lesser-known works, too. —Jillian Karande Karen Tei Yamashita contends with the Western canon in this astute, pitch-perfect, and wryly funny short story collection. Yamashita recasts Jane Austen characters as Japanese Americans navigating themes familiar to anyone who has read Austen and her contemporaries — social tension, familial obligation, clumsy personal growth, all of the mundanities that add up to meaning — through the lens of Japanese immigrant and Japanese American experiences. It's a genuine pleasure to read. —A.R. Hilarious and exquisitely written, this story collection released in 1997 immediately established Packer as one of her generation's premier writers of short fiction. And it's easy to understand why. From dueling Brownies troops in the first story to the darkly funny title story about a black student attending a predominantly white college, her stories plumb both the absurdity and the isolation inherent in belonging to the shrinking black middle class. —T.O. Girls suffer through growing pains in this fantastic debut collection published in 2010. A biracial preteen spends the summer with her white grandmother and cousin, learning more about the frosty relationship between her grandmother and her mother. A college student deals with an unexpected pregnancy. The main appeal of these stories lies in the pleasure of Evans' writing. Her prose is both wickedly funny and subtly devastating. —T.O. Riverhead, Dzanc, Mariner, One World, Picador, Penguin, Graywolf Five-Carat Soul covers a lot of ground, all of it unpredictable, exhilarating, and, often, hilarious. The short stories bounce from one unlikely protagonist to the next — from the antique toy dealer chasing a legendary train set owned by Robert E. Lee, to a captive lion making sense of the hierarchy of the zoo, to the one and only Abraham Lincoln — and each story, despite the foreignness of its characters' circumstances, expertly weaves in timeless themes. I love these stories individually, but all together they make for a wild and utterly delightful ride. —A.R. Bhuvaneswar is a *force* in her provocative debut, which centers on women of color who resist easy categorization — a therapist who is drawn to but disgusted by her young patient, a scholar desperate to justify her affair with her terminally ill best friend's husband, a woman remembering the girlfriend she abandoned when she accepted her arranged marriage. Bhuvaneswar fully inhabits them, breathing life into their dissonant, beautiful, complete selves. —A.R. Friday Black by Nana Kwame Adjei-BrenyahReading Friday Black is like being shaken awake. These stories exist in a sort of hyperreality — ordinary characters living in the not-so-unbelievable, Black Mirror–esque future of a culture that doesn't hesitate to commodify cruelty or monetize revolution. (See: "Zimmer Land," the story about an amusement park that allows guests to play-act their most violent urges.) Adjei-Brenyah skewers the ways we brush past racism and injustice, making the absurdity of the rhetoric around both impossible to ignore. —A.R. Set against the background of Denver, these stories follow indigenous women in relation to their home. In some cases the land holds histories these women long to escape; in others, it changes so rapidly as to disorient those who call it home. Fajardo-Anstine's prose blossoms on the page; her scenes and characters develop so vividly that they're likely to leave an impression lasting long after you stop reading. —A.R. Berlin's first posthumous collection, A Manual for Cleaning Women, got a lot of (deserving) praise, but I'm partial to the followup. Here we see Berlin's world — her time spent in Texas, Chile, and Mexico — filtered through evocative fiction. Her characters are utterly captivating — the moneymaking kids, the retired ambassador, the musicians, the actors, the addicts — and her scenery envelops you. But it's the early stories, those that follow the meandering adventures of kids just trying to fill their days, that are most vibrant. —A.R. Keret's stories range from dark to downright silly — there's the child in the title story who misunderstands the intentions of a man standing on the roof of a tall building, the strangers who meet up daily after work to share a joint on the beach, the increasingly absurd email exchange between a man desperate to bring his mother to an escape room that is unfortunately closed, and the owner of said escape room with a pretty big secret to hide. Each is beautifully wrought and rife with meaning — and slightly maddening in its ambiguity. —A.R. If even the prospect of short stories seems overwhelming, I recommend one of my most comforting reads — a book that is perfect if you want nothing more than to be swiftly and briefly transported to a more magical reality. The Book of Imaginary Beings is an encyclopedia of 116 "strange creatures conceived through time and space by the human imagination," both general (e.g., dragons) and specific (e.g., the Cheshire Cat). Forget about sitting down with it for a large chunk of time — it's better when you dip in and out. —A.R. There's a reason this book was everywhere — it's really very good. Machado's sharp, eerie, and often hilarious stories experiment with format in a way that feels genuinely new, dropping in theatrical asides to the reader, or structuring a narrative around Law and Order episode titles. Their darkness is playful until it's not, and that tipping point happens whenever the reader realizes the surrealist nightmares Machado has built around her female protagonists — worlds in which women's bodies are infected by the trauma they've witnessed, or made vulnerable by an epidemic of becoming ethereal — aren't quite so fantastical at their cores. If you haven't read it yet, now's the perfect time. —A.R. CORRECTIONLorrie Moore's full collected stories published in 2020. A previous version of this post misstated the publication date. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "famous short story,short stories for high school" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment