Explaining Bloody Bible Stories to Children | Adam Lee - Patheos

"Daddy, why is it called Passover?"

My son, now 4 years old and overflowing with questions, asked me that the other day. I hesitated over what to say to him.

A few years ago, before I became a parent, I would have thought this was an easy question. Most religious stories, even the ones presented as uplifting and instructive, have terrible morals.

Jesus' crucifixion reinforces the poisonous myth of original sin and the morally nonsensical idea that one person's misdeeds can be absolved by punishing someone else. The Old Testament's chosen-people theology promotes the dangerous and arrogant notion that there's one race God favors above everyone else. The belief in heaven and hell is a dehumanizing idea which holds that some people deserve eternal torture, and that good people will happily go along with this.

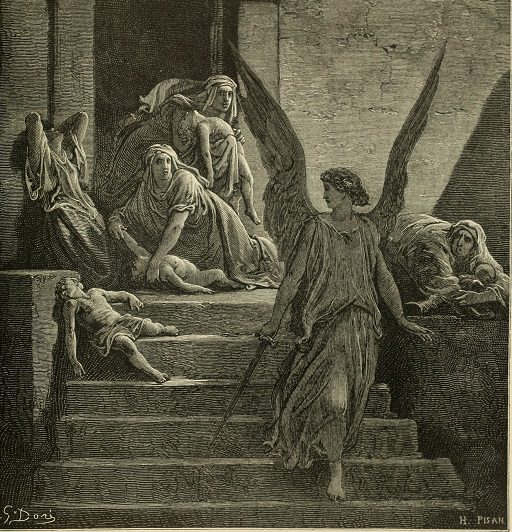

And Passover is the culmination of an episode that shows the God of the Old Testament at his most capricious, violent and vindictive, slaughtering the firstborn of Egypt for questionable reasons. As I wrote in "A Book of Blood":

After all, ancient Egypt was not a democracy. It was entirely Pharaoh's stubborn heart that was to blame – the ordinary Egyptian people had no part in this decision! What purpose did it serve to punish them? More, what purpose did it serve to punish their children? Among the people dead, many must have been young children, toddlers, infants, newborn babies. What responsibility did they bear for the Israelites' centuries-long captivity?

That hypothetical me-from-a-few-years-ago would have said these bloody folktales are only treated as positive examples because of the undeserved privilege that society grants to religion. He would have said that nonreligious parents ought to raise their children free from these superstitions, and that we have a duty to tell them the truth (in an age-appropriate way, of course – not something like, "Passover is a holiday that celebrates the time God killed thousands of children just like you!"), and not mislead them with palatable lies.

Now, it may sound like I'm winding up to disavow this viewpoint… but I'm not. In general, I still believe it's correct. There are good parts in the Bible and other religious scriptures, but there are many more brutal, bloody and awful parts, and we shouldn't confuse one for the other.

However.

The big complication is that my wife and I have been teaching our son about racial justice, and the Passover story, construed as an tale of liberation from slavery, is deeply interwoven with the history of racism and resistance in America. My son has a kids' biography of Harriet Tubman that he likes me to read to him. Something he's asked about is why Harriet Tubman was called "Moses" by the people she helped free.

There's no way to explain that connection without giving him an outline of the Passover story. And once I've told him that, how could I go on to say that the biblical Moses was a tribal warlord who served a murderous tyrant of a god? That would scramble the anti-slavery moral which I think, at this point in his life, is the more important one.

Explaining the "conventional" Passover story to my son was helpful in another way. Children have an innate drive to categorize, and sometimes they overlearn a rule. In one conversation about slavery and civil rights, he thought that Black people are the only group who've ever been treated unfairly, and he won't have to worry about that happening to him because he's white. When he said that, it was helpful to be able to teach him about his Jewish heritage and how people like us have also sometimes been targets of mistreatment and prejudice.*

None of this is to say I'm not going to tell him about the unsavory parts of the Passover story, or the Bible as a whole. I am. But when you're dealing with young kids, who tend to struggle with nuance, you have to give them the basic understanding (lies-to-children) before adding caveats that make the picture more complex.

An atom isn't literally a miniature solar system, with electrons orbiting the nucleus like planets orbiting a sun. But that picture, although incorrect in important ways, is a helpful metaphor that serves as a first step to acquiring a deeper understanding.

Similarly, you can use Passover as a parable to instill the core lessons that slavery is wrong and that people throughout the ages have sought liberty. It's true that explaining it at this level leaves out some important details, and if I were to stop there, that would be a problem. But the same is true of any historical figure or event. Real life is always messier and more ambiguous than the neat little morals we extract from it.

Christianity itself, with its complicated and paradoxical history in America, is the perfect example. It was both the imperial, colonizing, white supremacist religion that was used to justify the enslavement and mistreatment of Black people, and also the religion of those same oppressed people which gave them a poetry of resistance and freedom. To emphasize either element at the expense of the other would be to do an injustice to your audience.

In the end, this is what we told him (credit to my wife Elizabeth, who came up with this kid's-level explanation):

According to the story, Moses went to Pharaoh and said, "Let my people go!"

And the Pharaoh said no, so in the story, God did bad things to Pharaoh and the Egyptians to punish them for being enslavers because slavery is bad. The Jews had a special sign they put on their door so God would "pass over" their homes and only do bad things to the enslavers and not harm the slaves.

I'm not satisfied with this as a final answer, but raising and teaching a child is a lifelong endeavor. As he grows up and acquires a deeper understanding, I'm going to tell him more. I'm going to teach him about history and culture and all the world's pantheons of belief – but I'm also going to introduce him to the messy parts. I'll show him the parts of scripture that preachers skip over, the historical episodes that get left out of textbooks. In the end, he'll have to make up his own mind about what he believes, but I see it as my job to ensure he's well equipped to do so.

* Never mind, for now, the excellent archaeological evidence that neither the Egyptian captivity nor the Exodus happened. Literal historical truth versus myth and symbolism is another of those things we'll get around to.

Comments

Post a Comment